A disturbing new report by the National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) reveals widespread abuse and neglect at for-profit youth residential treatment facilities. The report, Desperation without Dignity, provides a comprehensive review of investigations by the nation’s Protection and Advocacy agencies and others in 18 states. It examines the history of the for-profit residential treatment industry, the private funding structure that fuels it, and discusses alternatives to residential placement that are both nurturing and provide the treatment that children and youth need.

Go to Press Release

Download “Desperation Without Dignity” PDF

Download Executive Summary (PDF)

Download Recommendations (PDF)

The National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) wishes to acknowledge the tremendous contributions to this report by members of the Protection and Advocacy (P&A) network – the staff who monitor these facilities, investigate reports of abuse, and represent the youth placed in them. In addition to doing the investigative and monitoring work which, informs this report, P&A staff drafted the report itself.

Production was coordinated by Diane Smith Howard of the National Disability Rights Network. David Hutt, David Card, and Eric Buehlmann reviewed and edited the report. Tina Pinedo edited and formatted the report. A special thank you to legal intern Marty Strauss, a second-year student at Harvard Law School, for his critical work on the details of this report.

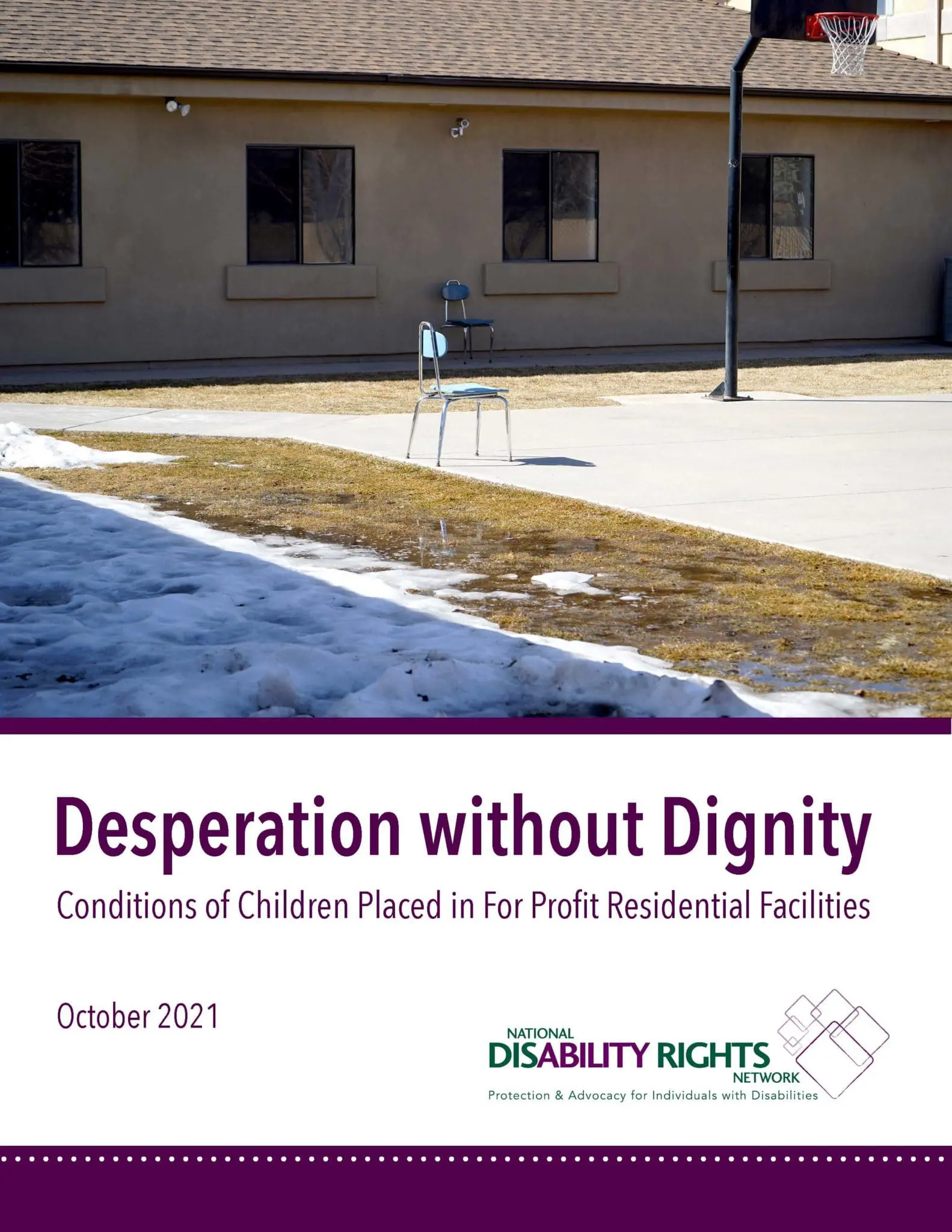

The photos included in this report are real. They were taken during visits to facilities discussed in this report by P&A staff. Photo credit goes to the P&As in Alabama, Arkansas, and Washington (ADAP, Disability Rights Arkansas and Disability Rights Washington).

The following federal agencies provided, in part, funding for the costs of this publication: the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (ACL), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the U.S. Department of Education, Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA). The contents do not necessarily represent the official views of ACL, SAMHSA, or RSA.

Dear Friends,

The past 30 years has been a time of unprecedented opportunity for children with disabilities. Our understanding of the services and support children need to thrive has steadily improved. Federal and state laws have been enacted to guarantee that the rights of children with disabilities are protected. Changing national attitudes favoring inclusion have meant more and more children with disabilities have found success living, working, and studying in the community with their families and peers.

Despite these achievements, some holdovers continue, such as the insidious practice of sending away some children and youth with disabilities for “treatment” at for-profit residential facilities. It’s a practice that often has dire consequences and harkens back to the institutions in the darker parts of our history. The suffocation death of 16-year-old Cornelius Frederick at a privately operated residential facility in April 2020 is just one of many examples.[1]

The nation’s Protection and Advocacy agencies, which make up the membership of the National Disability Rights Network, along with other advocates, have seen inside these facilities. In some, children quite literally do not receive enough food to grow normally, are given powerful drugs they do not need, and are housed in vermin infested buildings. Investigations across the nation have uncovered abuse — from broken bones, fight clubs, and sexual abuse by trusted staff, to forced isolation and shaming.

Children and youth with disabilities who end up in these facilities are often placed out of state and out of sight. They are far away from home, making it difficult for parents or guardians to monitor health and safety. They operate with little government oversight. Cases have been substantiated of the complete failure in some facilities to provide any mental health treatment, treatment that is the stated purpose of the placement of children in the first place and paid for at great taxpayer expense.

This must stop now. We must bring these children home.

While abuse and neglect of persons with disabilities occur in many settings, in this report we investigate the for-profit youth residential treatment industry and provide recommendations for alternatives for these children who are being sent away. We hope you find it helpful and informative.

Curtis L. Decker, J.D.

Executive Director

[1] Tyler Kingkade and Hannah Rappleye, “Cornelius Frederick: Warning signs missed before teen’s fatal restraint,” NBC NEWS (August 14, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/brief-life-cornelius-frederick-warning-signs-missed-teen-s-fatal-n1234660.

The suffocation death of 16-year-old Cornelius Frederick at a privately-operated residential facility in April 2020 focused the world on the plight of children and youth housed in for-profit residential treatment facilities (RFs).[1] Sadly however, these concerns are not new.

Protection and Advocacy (P&A) agencies, created by Congress in the 1970s to advocate for persons with disabilities in every state and territory, have learned through monitoring and investigating these facilities that the children placed in many RFs are not treated as people with value–with a human need for dignity. The P&A Network[2] has monitored, reported, investigated, analyzed documents and data, and recommended specific policy changes regarding these facilities nationwide and over the course of many years. The P&As’ work informs this report.

This problem is current, ongoing and is not limited to any one corporation or geographic region. As is documented in this report,[3] P&A investigations have uncovered abuse in for-profit residential facilities across the nation — from broken bones, fight clubs and sexual abuse by trusted staff, to forced isolation, shaming and the complete failure by some facilities to provide the mental health treatment that prompted placement in the first place. In some facilities, children quite literally do not receive enough food to grow normally and are housed in vermin-infested buildings. They are prevented from contact with their families and do not receive critical medical care in time to prevent serious injury. There are instances in which medication is administered as a “chemical restraint” to control behavior for staff convenience, rather than as intended to protect the health and safety of the child or others.

Facilities may not provide evidence-based treatment, such as cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and trauma-informed care due to cost or staff availability. The minimal psychotherapy that may be offered has little therapeutic benefit, since the foundation of psychotherapy—a trusting patient and provider relationship—is lacking in many of the for-profit RFs the P&As and state licensing agencies have investigated. Lack of meaningful therapy may exacerbate a child’s trauma and mental health condition, and a child’s refusal to participate in therapy may result in loss of privileges.

Restraint and seclusion should be utilized only as a last resort. It can be additionally traumatic for children with significant abuse histories. Yet routinely, P&A’s report that restraint and seclusion is systematically imposed on youth. Children are subject to extreme and illegal restraints as punishment rather than for their own health or protection and for non-threatening behaviors, such as verbally provoking staff.

Despite all these issues, RFs continue to make profit. ln recent years, privatization of private RFs for children and youth grew rapidly into a multi-million-dollar enterprise.[4] Although for-profit behavioral health facilities may be lucrative for investors, they often implement cost-saving measures that are detrimental to the vulnerable youth they serve.[5]

State and local governments routinely contract with these facilities, both in and outside their own states. This practice stems in part from the facilities’ cheerful and promising advertising, as well as the desperate shortage of community-based services that can provide the care these children need at home. The business model of for-profit RFs “banks on governments’ incapacity to create safe places for their most vulnerable children.”[6] These facilities exist because they purportedly meet a need that others will not.

RFs collectively generate millions of dollars per year, at times charging nearly double what governments would pay for the same services in-state.[7] The monetary incentives driving the operation of some RFs has even led to allegations of insurance fraud for filing claims for services not provided.[8] In one case, this resulted in a $4 million settlement between an RF and the state of Massachusetts.[9] A recent settlement by the U.S. Department of Justice with provider giant, Universal Health Services (UHS), resulted in an agreement to pay $117 million. The agreement resolved alleged violations of the False Claims Act “for falsely billing inpatient behavioral health services that were not reasonable or medically necessary and/or failed to provide adequate and appropriate services for adults and children admitted to UHS facilities across the country.”[10]

This recent focus on these facilities has resulted in tepid and scattered attempts at state legislation and oversight efforts, and a wave of reporting by media and advocacy by facility survivor groups and youth advocates, including high profile celebrity survivors.[11] The fact that advocacy has not resulted in more change may be both a testament to the power of this industry and the lack of a functional service system of community-based mental health supports that can provide alternatives.

Placing children in these facilities, especially once a state has notice of reported failures, is a violation of the states’ obligation to act in loco parentis (in the place of a parent), ensuring the safety of children in their care. This report will examine the rights violations endemic to for-profit RFs, discuss the financial structure supporting these facilities, and recommend specific solutions at the federal, state, and local level.

[1] Id.

[2] NDRN is the non-profit membership organization for the federally mandated Protection and Advocacy (P&A) agencies for individuals with disabilities. P&A have the legal authority to monitor and investigate allegations of abuse and neglect in specific types of facilities. The P&As were established by Congress to protect the rights of people with disabilities and their families. A P&A exists in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Territories (American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and there is a P&A affiliated with the Native American Consortium in the Four Corners region of the Southwest. Collectively, the 57 P&As are the largest provider of legally based advocacy services to people with disabilities in the United States.

[3] Citations not provided here are provided elsewhere in the report.

[4] Eileen O’Grady, Understaffed, Unlicensed, and Untrained: Behavioral Health Under Private Equity, Priv. Equity Stakeholder Project, p. 3.

[5] O’Grady, note 5, at 3.

[6] Curtis Gilbert & Lauren Drake, The Bad Place, APM Rep. (Sept. 28, 2020), https://www.apmreports.org/story/2020/09/28/for-profit-sequel-facilities-children-abused.

[7] See Gilbert & Drake, note 5.

[8] O’Grady, note 5 at 7.

[9] O’Grady, note 5, at 7.

[10] USDOJ. July 10, 2020, Universal Health Services, Inc. to Pay $117 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations | USAO-EDPA | Department of Justice

[11] See, e.g., Julia Reinstein, Paris Hilton Testified That She Was “Abused On A Daily Basis” At A Treatment Facility For Teens, BuzzFeed News (Feb. 9, 2021, 1:44 PM), https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/juliareinstein/paris-hilton-abuse-testimony-utah.

Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facility (PRTF): non-hospital facilities which have entered into an agreement with a state Medicaid agency for the provision of inpatient psychiatric services to Medicaid-eligible individuals under the age of 21.[1]

Qualified Residential Treatment Program (QRTP): One of four specific types of childcare institutions named in the Family First Prevention Services Act that may qualify for federal matching payments after a child’s first two weeks in that congregate care setting, affording a funding opportunity that other residential programs do not possess. The other three allowable childcare institutions are: (1) a setting specializing in providing prenatal, post-partum, or parenting supports for youth, (2) a supervised independent living setting, and (3) a setting providing high-quality residential care and support services to children who have been or are at risk of becoming sex trafficking victims.[2]

Residential Facility (RF): a residential placement for children and youth, often those diagnosed with mental illness, behavior challenges and/or intellectual/developmental disabilities.[3]

Youth Residential Treatment Facility (YRTF): a residential placement for children and youth. Used in some states as a generic term to describe all types of residential programs serving youth.[4]

[1] See What is a PRTF, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/downloads/whatisaprtf.pdf.

[2] What is a QRTP?, National Association for Children’s Behavioral Health, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/certificationandcomplianc/downloads/whatisaprtf.pdf (last updated Jul. 1, 2020).

[3] See NPI Lookup Residential Treatment Facilities, NPI, https://npidb.org/organizations/residential_treatment/ (last visited Aug. 17, 2021).

[4] For the purposes of this report, these facilities will be referred to as “RFs” (residential facilities) unless another designation is otherwise relevant. For example, PRTF’s have additional requirements, so there will be circumstances in which the fact that a facility is a PRTF will be important information for the reader.

- Alabama: Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program (ADAP)

- Arkansas: Disability Rights Arkansas

- California: Disability Rights California

- Illinois: Equip for Equality

- Iowa: Disability Rights Iowa

- Kansas: Disability Rights Center of Kansas

- Kentucky: Kentucky Protection and Advocacy

- Maine: Disability Rights Maine

- Maryland: Disability Rights Maryland

- Michigan: Disability Rights Michigan

- Montana: Disability Rights Montana

- New Jersey: Disability Rights New Jersey

- New Mexico: Disability Rights New Mexico

- North Carolina: Disability Rights North Carolina

- Ohio: Disability Rights Ohio

- Tennessee: Disability Rights Tennessee

- Utah: Disability Law Center of Utah

- Washington: Disability Rights Washington

A child at a for-profit youth Residential Facility (RF)[1] in Alabama summed up their dangers: “I don’t think any kids are safe here.”[2]

Although these facilities may advertise that they are structured to improve the mental health of children and youth, the abuse and neglect some children endure at for-profit RFs may worsen their existing mental and behavioral health issues, and in some cases may even lead to new issues, as children and youth leave the facilities more traumatized than when they first arrived.

A monitoring review at Sequel Youth and Family Services of Courtland, an Alabama for-profit RF, showed that, neglect and physical abuse—both staff-on-child and child-on-child—ran rampant. One boy told investigators that he saw “too many injuries to recall.”[3] The investigators documented feces and blood smeared on the walls and floors of the children’s rooms.[4] Although investigators alerted facility staff, the blood and feces were still there during a follow-up visit.[5]

According to a report by the State of North Carolina, at Anderson Health Services, a North Carolina RF, staff used zip-ties to restrain a 14-year-old girl for more than an hour in blatant violation of state and federal law.[6] The girl had a history of physical abuse, and her family told the media that her stay at that RF made her mental health worse, not better.[7] Ten staffers at this facility have been charged with child abuse since 2017, including allegations that the staff choked youths and punched them in the face.[8]

At Red Rock Canyon School,[9] a Utah RF, according to a lawsuit staff regularly insulted and physically abused youths, and allowed them to restrain each other with chokeholds.[10] Tragically, there are other examples of physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and endangerment at for-profit RFs across the country.[11] As explained further below, when there is scrutiny of a facility’s practices, in some cases the facility may close, discharge its residents, and reopen in another location or under another name.

This is not ancient history. As recently as January 2021, a class action lawsuit was filed against a facility operated by Devereux Advanced Behavioral Health. The lawsuit alleges that six children—three in Pennsylvania, two in Florida and one in California—who ranged in age from 8 to 17 at the time, were abused between 2003 and 2019 at a Devereux campus.[12] The lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia.[13]

The purpose of this report is to share what the P&As have learned in their work and make recommendations for improvement. The P&A system is a Congressionally-mandated national network of legally-based disability rights agencies whose mission is to, among other things, respond to and prevent abuse and neglect of people with disabilities and to enable full access to resources for people with disabilities such as inclusive educational programs, housing and health care. Federal law authorizes P&As to conduct monitoring activities and investigations in any setting that serves people with disabilities.[14] P&As have the authority to enter for-profit RFs and other profit and non-profit run facilities without advance notice, giving P&As a unique ability to see first-hand conditions faced by people with disabilities.

P&A agencies monitor RFs in part by visiting the facility, interviewing residents and staff, and documenting all areas of the facility to which persons with disabilities may have access, including common areas and personal rooms. If a P&A finds evidence of potential abuse or neglect, the P&A may commence an investigation. At that point the P&A may access resident records, facility records, and other information. P&As may choose a facility to monitor because the P&A has received complaints about the facility or because the facility is part of a regular rotation for routine monitoring.

Many years’ worth of information gathered during P&A monitoring and investigations informed this report. This information has been analyzed, reported, and often re-investigated by oversight agencies and others.

[1] This report focuses on the provision of services by for-profit RFs. While abuse and neglect of persons with disabilities occurs at all types of facilities, this report focuses on for-profit entities because of the financial motivations behind such entities and the number of investigations conducted and concerns raised by the P&As and other agencies. By focusing on for-profit PRTFs, we do not mean to suggest that abuse and neglect does not occur in other types of service models and facilities such as those run as private non-profit or public entities. Consideration of all such types of PRTFs was beyond the scope of this report.

[2] Monitoring Report for Sequel Youth and Family Services of Courtland, Ala. Disabilities Advoc. Program, p. 17 (July 2, 2020) (hereinafter “ADAP”).

[3] ADAP, note 74, at 2.

[4] ADAP note 74 at 42-43 (documenting in resident bedrooms “feces smeared on wall,” “feces on floor,” “blood smeared on wall,” and “blood smeared on window”).

[5] ADAP note 74 at 5.

[6] Liz Foster, Medical director at Union County mental health facility addresses shocking findings, WSOCTV (June 8, 2018), https://www.wsoctv.com/news/local/channel-9-uncovers-shocking-allegations-against-union-county-mental-health-facility/763538954/.

[7] Foster, note 22.

[8] NC Div. of Health Serv. Regulation, Plan of Correction, p. 97 (June 19, 2018); https://info.ncdhhs.gov/dhsr/mhlcs/sods/2018/20180706-140458.pdf.

[9] Jessica Miller, “Foster boy sues Oregon officials who sent him to Red Rock Canyon School in St. George,” Salt Lake Trib. (Nov. 21, 2019), https://www.sltrib.com/news/2019/11/21/an-oregon-foster-boy/.

[10] Miller, note 24.

[11] See, e.g., Gilbert & Drake, supra note 7; ADAP, supra note 18; Fred Clasen-Kelly, Kids in NC psych center abused, fed so little ‘your stomach will shrink,’ report says, Charlotte Observer (Nov. 13, 2018), https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article221541035.html.

[12] See Class Action Complaint & Demand for Jury Trial, Jines et al. v. The Devereux Found. et al., No. 2:21-cv-00346 (E.D. Pa. Jan. 26, 2021).

[13] Id.

[14] See The Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000, Pub. L. No. 106-402, S. 1809, 106th Cong.

The negative developmental impact of residential treatment on children

Children need “consistent, nurturing adults in their lives in order to form healthy attachments and to develop positive socio-emotional skills.”[1] Congregate care settings for children have been found to increase exposure to trauma and to negatively impact educational outcomes.[2] According to the Residential Treatment Center, there are 1,591 such facilities currently in operation in the United States.[3] However, due to disparities in licensure standards across states, the number is likely much higher.

It has been estimated that as of 2020, between 5 million and 6 million children worldwide reside in institutions, rather than in home-based settings.[4] Between 2009 and 2020, the use of congregate care for children in the United States decreased by 20-percent. Despite the known risks, however, some states still rely heavily on congregate care as a first-choice placement.[5] In 2006, 28 states reported deaths in residential treatment facilities and 49 states reported having investigated allegations of abuse and neglect, including sexual abuse.[6]

From a clinical perspective, residential treatment centers are healthcare facilities that employ a “behavior-modification paradigm” treatment modality. Services are provided within an institutional setting, and the amount and type of mental health and educational services provided depend on the facility.[7] However, according to the Government Accountability Office, some residential treatment programs employ misleading advertising practices, including statements about their level of oversight.[8]

Youth placed in congregate care and therapeutic foster homes “have significantly higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behaviors” such as “aggressive behavior, oppositionality, and conduct problems” than those in traditional foster care.[9] Both abuse and neglect have significant neurological impacts on the developing brain. Maltreatment “negatively impacts a young person’s capacity for optimal social and emotional functioning,” and it compromises long-term executive functioning.[10] According to Laura W. Boyd, Ph.D., “It is not enough to remove a child from the conditions of harm following complex negative events;” rather, “[e]motional, physical, cognitive, and social trauma must be addressed through effective treatment.”[11] If children and youth in need of treatment instead face abuse, it can compound with any existing trauma and lead to devastating consequences.

Mitigating factors can include screening for mental health needs upon entry to the residential treatment facility, including symptoms that suggest past trauma.[12] The Alliance for the Safe, Therapeutic and Appropriate Use of Residential Treatment (A START) provided a list of warning signs when placing a youth in a residential treatment center. A START recommends that caregivers avoid residential treatment programs that, among other things, use harsh and excessive discipline tactics such as seclusion; provide sub-standard therapeutic intervention; and provide sub-standard education.[13]

Congregate Care vs. Community-Based Treatment

Community-based care providers are largely lacking in many states across the country, and the ones that do exist may be insufficient to meet the complex needs of certain children. Although congregate care has “long been viewed as a viable placement alternative,” clinical guidelines suggest that “congregate care be reserved for the short-term treatment of acute mental health problems.”[14] Because there are insufficient treatment alternatives, children with mental healthcare needs are often placed into inpatient treatment settings such as for-profit RFs. As detailed in this report, a lack of oversight[15] and a perceived lack of placement alternatives make RF placement a “go-to” option for the responsible placing agencies.

Successful Treatment Interventions

Several treatment modalities have demonstrated benefits to children with mental and behavioral health disorders, including children with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression, and/or anxiety. Evidence-based treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), and psychotherapy.[16]

DBT focuses on providing therapeutic skills for mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness.[17] DBT has been shown to be effective in treating suicidal children and youth and those with self-injurious behavior; it has also proven to be helpful to youths involved in the juvenile justice system.[18]

Psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy, may be conducted in individual or group sessions and can help individuals process and cope with emotional difficulties and mental illness.[19] Psychotherapy supports treatment of a variety of mental and behavioral health issues.[20]

[1] What are the outcomes for youth placed in congregate care settings?, Casey Family Programs, Feb. 2, 2018 (available at https://www.casey.org/what-are-the-outcomes-for-youth-placed-in-congregate-care-settings/).

[2] Id.

[3] RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT CTR. (Jan. 28, 2021) https://www.residentialtreatmentcenters.me/.

[4] Van Ijendoorn, Marinus, et al., Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 2: a systemic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development, The Lancet, 606-633, 606 (Vol. 7, August 2020).

[5] Policy Brief, Chapin Hall & Chadwick Center, Using Evidence to Accelerate the Safe and Effective Reduction of Congregate Care for Youth Involved with Child Welfare, Jan. 2016 at 3.

[6] U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-08-696T, RESIDENTIAL FACILITIES: STATE AND FEDERAL OVERSIGHT GAPS MAY INCREASE RISK TO YOUTH WELL-BEING ii, 3 (2008). https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-08-696t.pdf.

[7] Laura W. Boyd, Ph.D., Therapeutic Foster Care: Exceptional Care for Complex, Trauma-Impacted Youth in Foster Care, State Policy Advocacy and Reform Center (SPARC) 1, Jul. 2013 (available at https://childwelfaresparc.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/therapeutic-foster-care-exceptional-care-for-complex-trauma-impacted-youth-in-foster-care.pdf).

[8] See generally U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-08-713T, Residential Programs: Selected Cases of Death, Abuse, and Deceptive Marketing 17-20 (2008) (statement of Gregory D. Kutz, Managing Director of Forensic Audits and Special Investigations). For example, one program in Texas asserted that “the National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs (NATSAP) ‘absolutely’ performs inspections of the[ir] program,” which was in fact not the case. Id. at 17. In another case, a referral service advised a (fictitious) potential client to lie to her daughter and tell her she would be attending “a college prep boarding school” rather than a residential treatment facility. Id. A different referral service stated on their website that “[w]e will look at your special situation and help you select the best school for your teen with individual attention,” when in fact the referral service recommended the same treatment facility—owned by the spouse of the referral service—to three (fictitious) potential clients whose children each had significantly different needs. Id. at 18.

[9] Policy Brief, Chapin Hall & Chadwick Center, Using Evidence to Accelerate the Safe and Effective Reduction of Congregate Care for Youth Involved with Child Welfare, Jan. 2016 (hereinafter Chapin Hall).

[10] U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Servs., Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Log No. ACYF-CB-IM-12-04, Information Memorandum 7 (2012).

[11] See Boyd, note 37.

[12] Chapin Hall, note 35, at 5.

[13] Facts and Warning Signs, Alliance for the Safe, Therapeutic and Appropriate Use of Residential Treatment (A START), Univ. OF S. Fla., http://astartforteens.org/assets/files/ASTART-Facts-and-Warning-Signs.pdf. See also Van Ijendoorn, Marinus, et al., Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 1: a systemic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development, The Lancet, 703-720 at 716 (Vol. 7, August 2020) (statistical analysis associating negative developmental outcomes with institutional care in children ages 0-18).

[14] Policy Brief, Chapin Hall & Chadwick Center, Using Evidence to Accelerate the Safe and Effective Reduction of Congregate Care for Youth Involved with Child Welfare, Jan. 2016 at 2.

[15] Curtis Gilbert & Lauren Drake, The Bad Place, APM Rep. (Sept. 28, 2020), https://www.apmreports.org/story/2020/09/28/for-profit-sequel-facilities-children-abused.

[16] See, e.g., Va. Commission on Youth, Collection of Evidence-based Practices for Children and Adolescents with Mental Health Treatment Needs, 23-32, http://vcoy.virginia.gov/pdf/Collection_HouseDoc7041513withcover.pdf.

[17] Psychol. Today, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/therapy-types/dialectical-behavior-therapy.

[18] Va. Commission on Youth, note 46, at 1, 28-32.

[19] APA, What is Psychotherapy?, https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/psychotherapy (Jan. 2019).

[20] Va. Commission on Youth, note 46, at 1, 28-32.

P&A agencies have the unique ability to shine a light on life in for-profit RFs and give residents the opportunity to tell the outside world what happens behind RF doors. P&As are empowered under federal law to conduct monitoring activities and investigations where people with disabilities receive services, including RFs.

Unlike most lawyers and organizations, P&As have the authority to enter schools, group homes, institutions, RFs and other facilities without advance notice, giving P&As a look at conditions faced by people with disabilities served in those settings. P&A agencies monitor RFs in part by touring the facilities, interviewing residents and staff, and documenting all areas of the facility to which persons with disabilities may have access, including common areas and personal rooms.

One example of the important work of the P&A in RFs is the work of Disability Rights Washington regarding children placed in RFs in Iowa and Illinois. In 2018, Disability Rights Washington published a report on Sequel Clarinda Academy in Iowa in response to growing concerns regarding the treatment program and use of restraints.[1] One youth receiving services at Sequel Clarinda Academy claimed that staff had dropped him, pushed him forward so that his face hit the floor, and bruised him in multiple locations, including his forehead, arms, and legs.[2] In November 2018, a 40-year-old staff member at Clarinda Academy pled guilty to sexual misconduct pertaining to a 17-year-old female resident.[3] The facility had falsely represented to the girl’s mother that only women would be working in the girls’ dorm.[4] Washington removed its residents from Clarinda Academy, and within two years, the Academy’s census reduced from 192 to 55.[5] Following the removal of residents by states such as Washington and California, as well as an investigation by the Iowa Department of Human Services, Sequel Clarinda shut down in early 2021.[6]

Another Washington youth, who had received treatment at Sequel Woodward Academy in Iowa, reported that he had once been put in restraints for over two hours with six employees on top of him.[7] In 2020, Washington decided to permanently stop sending children to Sequel-run facilities, as well as to remove children who had already been placed in those facilities, following these and other investigations across several states pertaining to allegations of abuse and neglect.[8]

An investigation by Disability Rights Ohio similarly factored into the State of Ohio’s decision to take action against a for-profit RF.[9] In July 2019 Disability Rights Ohio initiated a 9-month investigation and found that staff at Sequel Pomegranate had used physical abuse (punched children and used chokeholds) and painful restraint techniques to restrain them. The investigation also found that the environment was “poorly supervised, unstructured, [and] re-traumatizing.”[10]

In March 2020, the Columbus, Ohio Police were called to the facility following allegations of a riot among the residents.[11] According to news reports, at least 16 reports were submitted of juveniles who had harmed themselves with implements such as pieces of broken toilets and swallowing batteries.[12]

In December 2020, following allegations of violent assaults and improper restraints of children, the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (OhioMHAS) announced a settlement agreement that would require Sequel Pomegranate’s residential facility to immediately relinquish its license for a period of at least ten months. OhioMHAS Director Lori Criss stated, “the failure of staff to respond” to these events “created an environment in which clients were being violent towards each other and staff, resulting in physical abuse and neglect.”[13] The state subsequently entered into the settlement agreement with the RF, which stated that the residential facility would not be considered to be in “good standing” for licensure reinstatement unless there were no active complaints, investigations, unresolved findings, unresolved plans of corrections, or open administrative hearings for any of Sequel’s licensed facilities in Ohio”.[14]

In February 2020, during Disability Rights Ohio’s active investigation, OhioMHAS also threatened revocation of Sequel’s 20-bed acute psychiatric hospital program license located in the same facility, often serving youth from their residential program.[15] Sequel Pomegranate entered into an agreement with OhioMHAS to suspend new admissions to its acute psychiatric hospital for 120-days, making a series of proposals to retrain staff, increase trauma-informed practices, and reduce the use of restraint. The 20-bed acute hospital program reopened in January 2021.

Disability Rights Ohio continued to monitor the facility. In Ohio, Sequel has rebranded itself under the name Torii Behavioral Health. In September 2021, DROH received notification from Torii Behavioral Health Systems that they voluntarily relinquished all of its OhioMHAS licenses and certifications, including its license to operate a private psychiatric hospital. The acute hospital plans to close on October 8, 2021.[16]

Alabama provides yet another example of the problems uncovered at RFs. In 2020, a parent of a child who had received treatment at Sequel Courtland in Alabama sued the facility. The parent contended that the child, who was placed at the facility by the Alabama Department of Human Resources (ADHR) for mental health treatment, was abused and neglected by staff and peers.[17] The lawsuit followed an investigation by the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program (ADAP), the P&A for Alabama, that determined Sequel Courtland provided unsafe living conditions and perpetuated abuses of the residents by staff.[18] Following the ADAP investigation, the ADHR took corrective actions to address the allegations.[19] ADHR spokesperson Daniel Sparkman stated that corrective actions included “companywide staff training and renovations/enhancements of the living areas, as well as the physical properties.”[20]

In 2019, a New Mexico facility called Desert Hills, run by the for-profit Acadia corporation, was shut down due to systemic allegations of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse perpetrated against the youth by staff members.[21] New Mexico’s Children, Youth, and Families Department (CYFD) worked in conjunction with Disability Rights New Mexico (DRNM), the NM P&A, to investigate these allegations and advocate for safe and effective discharge planning in the midst of what turned out to be a mass removal of children, often only to be placed at other Acadia-run facilities.[22]

These examples show the necessary oversight role of the P&As, but the P&As are not sufficiently funded to ensure the safety of all children and youth placed in RFs. The nationwide network of P&A agencies receive funding through nine distinct funding streams. Combining this funding means that the P&As provide advocacy services to people with all types of disabilities, no matter the age, and on all issues that can impact people with disabilities – education, employment, community integration, abuse and neglect, housing, transportation to name a few. The amount of funding does not rise to the level of demand placed on the P&As, so each P&A must set priorities, with stakeholder input, of issues that will be addressed by P&A advocacy with that program’s funding. Ultimately, this means that some issues that would positively impact the disability community cannot be addressed due to a lack of funding.

While P&As theoretically have the ability to advocate for people with all types of disabilities on all topics, funding limits their ability and reach. In order to ensure that each P&A has sufficient funding to address a particular topic, creating a specific funding stream focused on that particular topic, issue, population has worked most efficiently and effectively. Once the P&As have dedicated funding, they can advocate on that topic, issue, or for a particular population without having to compete with the multitude of other issues that need to be addressed through a particular funding stream.

As this report has clearly explained, there is a need for well supported, vigorous, independent oversight of these for-profit providers.

[1] Curtis Gilbert, California hands Sequel a major setback, Am. Pub. Media Reports, Jan. 28, 2021 (available at https://www.apmreports.org/story/2020/12/14/california-hands-sequel-a-major-setback).

[2] Rachel Nielsen, Washington Foster Kids Detail Abuse at Sequel Group Homes, InvestigateWest, Dec. 2, 2020 (available at https://www.invw.org/2020/12/02/washington-foster-kids-detail-abuse-at-sequel-group-homes/).

[3] Lee Hood, For-profit Iowa academy for troubled youth hired felon who raped a student, The Des Moines Register, Nov. 28, 2018 (available at https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/investigations/readers-watchdog/2018/11/28/profit-academy-tr-academy-troubled-youth-hired-felon-who-raped-student-lawsuit-alleges/2138992002/); see also Multi-Million Fines Insufficient to Curb Abuse in For-Profit Behavioral Health Industry, Citizens Commission on Human Rights, Florida, Jul. 31, 2019 (available at https://www.cchrflorida.org/multi-million-files-insufficient-to-curb-abuse-in-for-profit-behavioral-health-industry/).

[4] Id.

[5] Curtis Gilbert, California hands Sequel a major setback, Am. Pub. Media Reports, Jan. 28, 2021 (available at https://www.apmreports.org/story/2020/12/14/california-hands-sequel-a-major-setback).

[6] Joaquin Palomino, Sara Tiano & Cynthia Dizikes, After abuse probe, another Sequel-run program that housed California youth will close, Laredo Morning Times, Feb. 8, 2021 (available at https://www.lmtonline.com/bayarea/article/After-abuse-probe-another-Sequel-run-program-15934785.php).

[7] Rachel Nielsen, Washington Foster Kids Detail Abuse at Sequel Group Homes, InvestigateWest, Dec. 2, 2020 (available at https://www.invw.org/2020/12/02/washington-foster-kids-detail-abuse-at-sequel-group-homes/).

[8] Curtis Gilbert, Washington becomes latest state to ditch Sequel, Am. Pub. Media Reports, Dec. 9, 2020 (available at https://www.apmreports.org/story/2020/12/09/washington-becomes-the-latest-state-to-ditch-sequel); see also Washington’s Out-of-State Youth Plead: Let Us Come Home; Report and Recommendations, Disability Rights Washington, https://www.disabilityrightswa.org/reports/let-us-come-home/, (Oct. 2018).

[9] Curtis Gilbert, California hands Sequel a major setback, Am. Pub. Media Reports, Jan. 28, 2021 (available at https://www.apmreports.org/story/2020/12/14/california-hands-sequel-a-major-setback).

[10] Disability Rights Ohio, DRO Investigates Systemic and Cultural Issues at Sequel Pomegranate Health Systems (available at https://www.disabilityrightsohio.org/news/dro-investigates-systemic-and-cultural-issues-at-sequel-pomegrante-health) (last visited Mar. 9, 2021); see also https://disabilityrightsohio.org/assets/documents/sequel-pomegranate-report-branded-final-edits.pdf.

[11] Bennett Haeberle, Children removed from Sequel Pomegranate one month after state threatened to revoke license”, 10 WBNS, Sept 2, 2020, (available at https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/children-removed-from-sequel-pomegranate-the-move-happened-one-month-after-state-threatened-to-revoke-license/530-08cec13c-87f6-488d-a665-31bb32e592a8)

[12] Bennett Haeberle, State requires Sequel Pomegranate to relinquish its license citing ‘recurring incidents’, 10 WBNS, Sep. 18, 2020, (available at https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/state-agency-revokes-license-of-sequel-pomegranate-citing-recurring-incidents/530-5dd9cd1c-1bbf-4c67-a7aa-655bf0e4b951).

[13] Bennett Haeberle, State requires Sequel Pomegranate to relinquish its license citing ‘recurring incidents’, 10 WBNS, Sep. 18, 2020, (available at https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/state-agency-revokes-license-of-sequel-pomegranate-citing-recurring-incidents/530-5dd9cd1c-1bbf-4c67-a7aa-655bf0e4b951).

[14] Curtis Gilbert, California hands Sequel a major setback; see also Bennett Haeberle, State requires Sequel Pomegranate to relinquish its license citing ‘recurring incidents’, 10 WBNS, Sep. 18, 2020, (available at https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/state-agency-revokes-license-of-sequel-pomegranate-citing-recurring-incidents/530-5dd9cd1c-1bbf-4c67-a7aa-655bf0e4b951).

[15] Bennett Haeberle, Sequel Pomegranate resumes treating teens months after facility was essentially shut down, 10 WBNS, Jul. 14, 2021, (available at https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/sequel-pomegranate-resumes-treating-teens-months-after-facility-was-essentially-shut-down/530-aa86390e-9ef3-4659-94d2-fbef2d2357d5)

[16] Bennett Haeberle, Embattled psychiatric facility for teens formerly known as Sequel Pomegranate tells state it will close, 10 WBNS, Sept.16, 2021, (available at https://www.10tv.com/article/news/investigations/10-investigates/sequel-pomegranate-tells-state-it-will-close/530-5ec3694d-29af-46c5-92c7-d06e4310e85a)

[17] Sara E. Teller, Alabama father brings lawsuit against Sequel facility alleging staff abused his son, LegalReader.com, Jan. 1, 2021 (available at https://www.legalreader.com/child-endured-abuse-at-alabama-sequel-facility-lawsuit-says/).

[18] See ADAP, note 74.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] See Cynthia Miller, Agency moves to shut down ‘archaic’ facility, attitudes, Santa Fe New Mexican (Feb. 17, 2019), https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/agency-moves-to-shut-down-archaic-facility-attitudes/article_696e74b8-c883-5926-8542-99c7ea755551.html; https://www.bizjournals.com/nashville/news/2019/04/08/acadia-facility-shuttered-amid-allegations.html.

[22] Miller, Id.

Abuse

As described in the list of examples above, physical, sexual, and psychological abuse are present at many RFs. The perpetuation of abuse, coupled with insufficient accountability for such behavior, leaves already vulnerable youths subject to re-traumatization and exacerbation of their behavioral and mental health symptoms. As the examples in this report indicate, abuse in RF’s is not limited to any one geographic region of the U.S. or to any one provider.

The abuse of children at RF’s has not been resolved. As mentioned above, as recently as January 2021, a class action complaint was filed against Devereux Advanced Behavioral Health.[1]

P&A reports have significant consequences, so it is critical that they be correct. Procedures have been put into place at each P&A to ensure accuracy. For example, P&A staff have techniques to verify reports of abuse by children, youth, and staff in these facilities. To ensure accuracy in reporting, practiced investigators at ADAP, the Alabama P&A, take the following steps (among others):

- ADAP staff educate children and youth up front about steps used to protect their identities to encourage a sense of security and foster honesty in reporting

- When ADAP staff interview most or all of the children in a particular program, they look for consistencies and inconsistencies in the stories. They ask the same set of questions of all children to establish a consistent baseline. This type of questioning exposes patterns of problematic practices and identifies particular staff who may be engaging in abuse/neglect.

- ADAP staff verify, with proper permission, as much as possible through record reviews, follow up interviews and video surveillance data. For example, when a boy residing in a RF reported being slammed against a wall, ADAP staff initiated an investigation and viewed surveillance video for that day that corroborated his story. When children and youth reported being “football tackled” this technique was consistent with what was reflected on the video footage.

- Investigations are unannounced. ADAP staff interview individual children and youth who live on the same unit as quickly as possible to prevent them from communicating with each other.

- When camera footage is not available, ADAP staff conduct follow up interviews with witnesses and compare incident reports and other documentation to identify similarities in injuries or other aspects of the report.

Physical Abuse

“I don’t feel safe.”[2]

Physical abuse, often masked as punishment or a control tactic, is not uncommon in RFs. Although some incidents begin as restraint and quickly escalate into physical abuse, children also report more direct examples of physical abuse as well, such as dragging, punching, and throwing or “slamming” them against walls or the floor.[3]

Youth report physically fighting with and inflicting injury on each other in staff members’ absence, while staff members watch, and/or as a result of staff members allowing youths to fight each other.[4] A boy at a RF in Alabama told ADAP that he had bruises after being hit by a peer and did not feel safe at the facility.[5]

Another boy at the same facility said that he was kicked in the face and had to have stitches after a fight with a peer.[6] Other boys described calling out to staff for help but staff was “too old” to respond.[7] In another incident, in which one boy reportedly started beating another boy and staff declined to intervene, other residents reportedly had to pry the boy off his peer.[8] In some instances, children are forced to share rooms with their abusers. In a North Carolina facility, staff placed a child in a room with another resident who had given him a black eye.[9]

Sexual Abuse

Children in RFs across the country report sexual assault at the hands of staff. An investigation by The Imprint and San Francisco Chronicle revealed that staff at Clarinda Academy[10] had been accused of punching, kicking, choking, and sexually assaulting youth at the facility.[11] A male Clarinda staff member reportedly raped a seventeen-year-old girl and pled guilty to sexual misconduct with a juvenile.[12] In 2017, an employee at Three Springs[13] was accused of, and subsequently pled guilty to, having sexual contact with a thirteen-year-old boy.[14] In March 2014, a 29 year-old staff member at Sequel Red Rock Canyon School in Utah was convicted of forcible sexual abuse after abusing three male students at the facility.[15] In January 2018, a 38 year-old staff member of Sequel Northern Illinois Academy pled guilty to three counts of criminal sexual assault on an adolescent over whom he held a position of trust and authority.[16]

According to a year-long investigation by American Public Media Reports, there are at least twenty documented cases since 2010 in which government investigations concluded that Sequel staff engaged in sexual or romantic relationships with residents.[17]

Children in RFs also report sexual violence committed by their peers. Some RFs specialize in treating youth who have been adjudicated as sex offenders.[18] These youth need more supervision, not less. As described below, staff do little to prevent the violence and are slow to interrupt and stop it. At one RF, several boys reported that older boys sexually prey on the younger boys making comments such as: “you better keep that little one from over here or I’ll snatch ‘em up.”[19] Another boy reported that he did not feel safe because boys were “doing sexual stuff” and that one boy “shows his stuff” and touches him inappropriately when the boys are in line.[20] The boy further said that he had reported these incidents to multiple staff on multiple shifts but they do not believe him and thus, the activity continues.[21]

Emotional Abuse

“If your parents really wanted you, y’all would be home.”[22]

Children at two RFs in Alabama report being subjected to a near-constant barrage of verbal abuse from staff. Staff curse, yell, make demeaning and derogatory comments, insult and make fun of the children. They threaten and intimidate them and even instigate arguments among residents and with staff.[23] For instance, at a Sequel facility in Alabama, girls reported being called “f*ng fat,” “f*ng ugly,” “bitch,” stupid,” and “ignorant.”[24] Multiple other girls reported that when they attempted suicide, they were told by staff that they should try again.[25]

A photo box sits beside a bed of a youth living at a RF.

At another Alabama RF, boys similarly reported being called names, being taunted, and being threatened by facility staff.[26] For instance, one boy reported that staff told him to “Get the f* out of my face!” and that caused him to have flashbacks to fights with his dad.[27] Another boy reported that staff told him “you ain’t never gonna be nothing” and “you gonna go to jail.”[28] Another boy said that there were lots of boys harming themselves, trying to commit suicide, trying to elope, fighting, and staff making residents angry on purpose so that staff could restrain them.[29]

RFs may fail to provide appropriate trauma-informed care following incidents of self-harm and suicide attempts/ideations.[30] For example, one boy at the Sequel facility in Alabama reported that he was one of many boys who had tried to kill himself, and that although he had tried to hang himself ten times, he was not able to see his therapist after the suicide attempts.[31]

Restraint and Seclusion

Lakeside Academy, a for-profit RF in Michigan, made headlines in May 2020 when 16-year-old Cornelius Frederick was killed by staff during a restraint.[32] Cornelius died of asphyxiation after two Sequel staff members sat on his chest and abdomen for nearly ten minutes while he cried that he could not breathe.[33] A third Sequel staff member allegedly witnessed the abuse but did not intervene or seek help for Cornelius.[34] According to a state report, staff restrained Cornelius simply because he threw a sandwich.[35]

In June 2020, the three staff members were charged with causing Cornelius’s death.[36] The two workers who restrained Cornelius were charged with the felony offense of involuntary manslaughter as well as with two counts of child abuse.[37] The third staff member was charged with one count of involuntary manslaughter and one count of child abuse after failing to seek, obtain, or follow through with timely medical care after witnessing the restraint.[38] The restraint was captured by video footage that, according to a lawsuit filed on behalf of Cornelius’s aunt, showed the staff “placing his/her weight directly on [Cornelius’s] chest for nearly 10 minutes as [he] lost consciousness.”[39] According to the Office of the Medical Examiner in Kalamazoo, MI, Cornelius Frederick died within two days following cardiac arrest, and his death was determined to be a homicide resulting from “restraint asphyxia.”[40]

Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) investigated his death and found ten licensing violations at Sequel Lakeside.[41] The MDHHS Division of Child Welfare Licensing subsequently began the process of revoking the facility’s license.[42] In June of 2020, the Governor of Michigan ordered MDHHS to ensure that Sequel is not providing services at any facility licensed by the department.[43]

Facilities use a variety of physical holds or physical restraints. The majority of crisis intervention programs provide training on physical holds in one or more of the following areas: (a) protection and release, (b) physical escorts, (c) standing restraints, (d) seated restraints, and (e) prone (face-down) floor restraints.[44] Providers often use euphemisms to describe restraint and seclusion practices, such as “therapeutic holds” and “reflection rooms.”

Federal regulations, called the Conditions of Participation (CoP), specify the manner in which Medicaid funds may be used in PRTFs that receive Medicaid. The CoP’s identify three general types of restraint:[45]

- “Mechanical restraint” is “any device attached or adjacent to the resident’s body that he or she cannot easily remove that restricts freedom of movement or normal access to his or her body.”[46]

- “Personal restraint” is “the application of physical force without the use of any device, for the purpose of preventing free movement of a resident’s body. The term personal restraint does not include briefly holding without undue force a resident in order to calm or comfort him or her, or holding a resident’s hand to safely escort them from one area to another.”[47]

- “Drug used as a restraint” is “any drug that (1) [i]s administered to manage a resident’s behavior in a way that reduces the safety risk to the resident or others; (2) [h]as the temporary effect of restricting the resident’s freedom of movement; and (3) [i]s not a standard treatment for the resident’s medical or psychiatric condition.”[48]

- “Seclusion is the involuntary confinement of a patient alone in a room or area from which the patient is physically prevented from leaving. Seclusion may only be used for the management of violent or self-destructive behavior.”[49]

The CoP permit restraints only as an intervention of last resort, and only in an emergency safety situation to prevent a resident from harming themself or others.[50] The CoP explicitly prohibit any form of restraint used as a means of coercion, discipline, convenience, or retaliation.[51] Further, restraints must be “performed in a manner that is safe, proportionate, and appropriate to the severity of the behavior, and the resident’s chronological and developmental age; size; gender; physical, medical, and psychiatric condition; and personal history (including any history of physical or sexual abuse)”[52] and must not result in harm or injury to the resident.[53]

The decision to use restraint or seclusion must be an individualized determination made based on the context and facts at the moment to ensure the safety of the resident or others and must cease once safety can be ensured.[54] Additionally, states may have their own laws which regulate the use of certain types of interventions. In some cases, state laws may be more limiting than federal law.

Due to their specific Medicaid/funding restrictions[55] PRTFs,[56] which are a specific type of RF, must abide by the CoP. However, data obtained from Serious Occurrence Reports, which PRTFs are required to complete in some circumstances,[57] and on-site monitoring visits by P&A investigators demonstrate that some PRTFs fail to follow these requirements and are overly reliant on restrictive and dangerous interventions such as restraints and seclusion.

Harm

P&As report that providers justify the use of seclusion and restraint as necessary, therapeutic techniques that ultimately reduce undesirable behaviors. However, there is no validated research to support such claims; rather, study after study demonstrates the detrimental effects of using seclusion and restraints.[58]

Physical harm is common during restraint. As discussed below, restraint is rarely, if ever, a non-violent event in which the risk of injury is minimal. For example, North Carolina regulators cited a PRTF for violations of the CoP when a staff member’s attempt to implement a restraint resulted in the fracture of a child’s orbital bone.[59]

At another PRTF, the regulators documented:

| A door at an RF with damage. |

“[LPN], Nurse: 7/16/2020: Nurse, [LPN] reported that on 7/13/2020 around 8:30pm, she observed [Client #1] hitting the wall and as a result [Staff #1] and [Staff #2] attempted to place [Client #1] in a therapeutic hold; to prevent [Client #1] from harming herself. The therapeutic hold was improperly performed; as [Client #1] hit and kicked staff ([Staff #1 and Staff #2]) to avoid being placed in a restraint. The therapeutic hold failed as [Staff #1], [Staff #2] and [Client #1] fell to the floor; after they fell, [Client #1] grabbed and pulled [Staff #1’s] hair. While on the floor [Client #1] continued to kick and yelled out, she was unable to breathe and for [Staff #1] to remove her knee from her face. Nurse, [LPN] began to assist by placing her hand in [Client #1’s] hand to release [Staff #1’s] hair from [Client #1’s] hand as she continuously asked [Staff #1] to remove her knee from [Client #1’s] neck. [LPN] then was able to remove [Staff #1’s] hair from [Client #1’s] hand and [Staff #1] was able to remove herself from [Client #1]”

After the incident, Client #1 was assessed and had injuries that included reddened areas on the left side of the upper body, neck and chin and swelling, swelling/redness to right 2nd, 3rd and 4th finger, discomfort to left thumb and bruising/discoloration on left upper arm.[60]

Trauma is perhaps the most common of the adverse effects of seclusion or restraint.[61] Trauma is “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”[62] During the traumatic event, youth may experience terror or helplessness; they may vomit, have a racing heart, or lose control of their bladder. The event can be frightening, as one or more adults hold the youth against his will, or drag her into a seclusion room. The situation may become further complicated as the youth, already operating at a high level of arousal, reverts to the “fight or flight” instinct and may be unable to calm themselves or process verbal directives from staff.[63] This may result in new, ineffective and dangerous control behaviors by the staff when the youth does not comply, respond, or otherwise behave as desired by staff.[64]

As is found in P&A monitoring described in this report, facilities continue to rely on restraint to manage and modify behavior in residential settings. A study from 2005 estimated the cost of one episode of restraint to be $302 – $354 based on a time/motion/task analysis.[65] These funds could be better spent hiring and retaining qualified behavior specialists to provide treatment to the children placed in RFs, instead of relying on traumatizing, dangerous interventions that cause injury to children and staff.

Prone Restraint

Prone restraint is a physical restraint during which an individual is forcefully moved from standing to lying face down on the ground. Two or more staff will then secure the arms and legs of the individual and hold him or her face down until calm. Staff initiating prone restraint are told to avoid putting pressure on the individual’s back as this can “inhibit breathing due to postural asphyxia, a form of asphyxia that occurs when one’s position prevents them from breathing adequately.”[66] The use of prone restraint in particular has been discredited over the last decade as incidents of severe injury or death have occurred with prone restraint.[67] Such incidents have been documented recently in several high-profile cases, such as those of Cornelius Frederick and George Floyd.[68]

Due to the dangers associated with this type of restraint, more than 30 states have already banned the use of prone restraints in public schools;[69] yet many states have yet to extend protections to children and youth in facilities. For example, in 2011, the Tennessee legislature signed into law the Tennessee Special Education Behavioral Supports Act[70] which aims to reduce restraint and isolation in public schools through encouraging the utilization of functional behavior assessments and behavior intervention plans to mitigate complex challenging behaviors. However, this law does not apply to special education- eligible children in residential facilities, even if they attend a school licensed by Tennessee’s Department of Education.

State Examples of Restraint and Seclusion

Alabama

During an extensive monitoring visit over multiple days at a for-profit RF in Alabama, the P&A received numerous reports of violent and illegal restraints.[71] One boy described his head being caught on a nail in the wall during a restraint;[72] another said he was picked up and slammed on his stomach onto the concrete.[73] A boy who had visible gashes to his head said that facility staff had slammed him against a wall the previous night.[74] Another boy reported being “football tackled” by staff after kicking a door.[75]

At another for-profit RF in Alabama, girls reported similar incidents to the P&A.[76] One girl reported that male staff repeatedly enter girls’ bedrooms (where there are no cameras) and put them in violent “containments.”[77] Another girl reported that when she refused to sleep in the hallway, she was forcibly dragged out of her room, thrown on the floor and then up against a wall, and suffered injuries to her head.[78] A third girl reported that facility staff forced her against a wall for making a comment to a staff member.[79] The girl attempted to defend herself but the “staff member picked her up, slammed her onto the ground, and placed his weight on her by putting his knee into her back, causing significant pain and trouble breathing.” The staff member “did not relent until forced off her back by other staff.”[80] The incidents reported by these children are physically abusive.

Illinois

A recertification survey completed in December 2019 by the Illinois Department of Public Health revealed that Northern Illinois Academy (NIA) in Chicago, a Sequel facility, was, among other findings, not in compliance with the CoP regarding restraint use.[81] As a result, the Washington County Department of Children, Youth, and Families reported a halt on referrals to Sequel facilities stating “the deficiencies are so serious that they constitute an immediate threat to patient health and safety.”[82] As of September 2020, Washington still had three children placed in Sequel Northern Illinois Academy.”[83] Washington placed the children and youth ignoring the warnings.

Equip for Equality (EFE, the Illinois P&A) filed a late 2020 complaint to the State about on-going concerns at Northern Illinois Academy and the State asked EFE to conduct a complete review of the facility, which EFE commenced in early 2021. At that time, there were a total of 72 children/youth there, of whom about 10 were from out-of-state. EFE completed a comprehensive report that included concerning findings about youth safety, restraint, seclusion, and quality of treatment. This report was central to Illinois’ decision to remove all state and locally funded youth from the facility and subsequently Northern Illinois Academy was completely closed by early August 2021.[84]

Iowa

Disability Rights Washington[85] and Iowa, the P&As in those states, conducted joint monitoring visits to the Clarinda Academy in Iowa, and DRWA completed a subsequent systemic investigation. Children at Clarinda, a for-profit RF, reported excessive and inappropriate physical restraint on a daily basis.[86] Several children reported that staff “just drop you.”[87] Another child reported being grabbed and forced to sit on the ground in a forward folded position so that the child’s head hit the ground and the child’s glasses broke.[88]

Michigan

Prior to Cornelius Frederick’s death, Sequel had come under scrutiny for improperly using restraint and had previously stated that it would integrate training on proper restraint methods,[89] such as Ukeru.[90] Yet, despite Sequel’s promises of proper training, its staff have violated the Ukeru guidelines. For example, during the restraint that led to Cornelius’s death, one staff member got off the boy to retrieve a Ukeru pad, and then propped it against a nearby table[91] while the boy asphyxiated under body weight restraint.[92]

Ohio

Disability Rights Ohio (DRO), after receiving disturbing reports of physical abuse by staff, peer-on-peer bullying, and bullying by staff, conducted a nine-month investigation at a for-profit PRTF.[93] Children at the facility reported that “[t]hey (staff) put their elbows in our jaws and tell us to stop talking . . . Our arms are up in such a way that they can get broken or our shoulders pop out of place . . . Staff throw kids against walls.”[94] Facility leadership informed DRO that staff were going to be trained on safer, trauma-informed crisis management.[95] When DRO visited the facility five months later, staff expressed confusion about training and said “it’s not being used yet.”[96]

Alternatives to Restraint

Restraints are not the only way, nor are they the best way, to improve youth behavior and ensure safety. According to the Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, there are a number of less intrusive and low/cost-free strategies and approaches that can be implemented to mitigate the need for emergency intervention.[97] Preventative, or antecedent-based, interventions focus on arranging the child’s environment to reduce the likely occurrence of a challenging behavior.[98] Antecedent-based interventions can include creating structured routines and schedules, modifying the setting to reduce identified triggers, embedding personal interests in tasks to increase engagement, avoiding demands that may elicit challenging behaviors, and offering choice. Additionally, residential programs that have had success in reducing the use of restraint and isolation also employ additional strategies such as implementation of training curricula to promote change in practice such as models of care, crisis prevention, or dispute resolution; creation of a stronger system of staff supervision; and use of compensation or incentives to encourage staff to obtain additional training.[99]

Reporting

The safety of children and youth is jeopardized when staff do not report data in compliance with legal requirements. As described below, staff may fail to document and report the use of restraint or seclusion as they are required to do or may fail to document all of the required information, such as the time the intervention began and ended, or key details of the emergency situation that led to the use of seclusion or restraint. This information is key to an effective post restraint review, one that prevents the need for future restraints, and evaluates the need for policy and training reform.

Disability Rights North Carolina, the P&A for that state, found that for-profit RFs fail to submit the required Serious Occurrence Reports (SORs)[100] to the P&A and/or state regulatory agency. A 48-bed for-profit PRTF in North Carolina was cited three times in a six-month period for failing to submit SORs to DRNC.[101] The North Carolina State Survey Agency identified nearly 900 instances of seclusion or restraint at the PRTF over the course of one year (870 in the one-year period and 1000 in one year and a quarter).[102]

Overuse and Misuse of Psychiatric Medication

P&As have found instances of overuse and misuse of psychiatric medication during monitoring visits at both youth residential facilities and also at for-profit psychiatric hospitals that treat children. As described below, these are not “one off” circumstances and have the potential to cause great harm to children.[103]

The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry’s guidelines to providers describing best practices for prescribing psychiatric medication to children and adolescents recommends that psychotropic medications and polypharmacy for children and youth be used only in limited circumstances.[104] Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved some psychotropic medications for use in youths,[105] many psychotropic medications prescribed to children are not approved for use in young age groups.[106] Psychotropic medications also pose unique health risks to children because young people lack the liver and kidney capacity required to metabolize psychotropic medications.

The long-term effects of psychotropic medication use in youth are largely unknown, and the limited studies that have been conducted tend to connect psychotropic medication use in youth to increased health problems into adulthood.[107]

| A mattress sits in the corner of a large room at an RF |

Antipsychotics, a dangerous class of psychotropic drugs, are particularly harmful to youth.[108] The cardiovascular metabolic effects and central nervous system depression associated with antipsychotics can cause life-threatening conditions in youths.[109] For example, a 2018 study linked administration of a high dosage of antipsychotic drugs to a significantly increased risk of sudden unexplained death for children and youth.[110] Data also suggest that youth experience the known adverse effects of antipsychotics more than adults.

Medications prescribed and used for “off-label” purposes have not specifically been approved by the FDA to treat the particular conditions for which they may be prescribed; they have not undergone the same clinical trial procedures as medications approved for specific purposes.[111] The side effects and overall safety of off-label drugs are therefore less certain.[112] The immediate and long-term risks associated with uncertainty about a drug’s safety are heightened for children and youth, as data on use of these drugs in youth are largely lacking as compared to data for adults.[113] Yet, off-label drug use represents approximately 50-75% of all pediatric medication use, including for psychotropic medications.[114]

Polypharmacy, or the use of multiple medications on one patient,[115] is associated with adverse effects and poor health outcomes because of an increased risk of dangerous drug interactions and other harmful side effects.[116] The potential dangers of polypharmacy are heightened by off-label drug use.[117] Children at for-profit RFs[118] have reported instances in which staff administer the same polypharmacy medication regimen to all residents, regardless of individual mental or behavioral health conditions and needs.[119]

Youth are at a higher risk for adverse effects of polypharmacy than adults, and youth under age 10 are particularly vulnerable.[120] Despite the adverse health risks, polypharmacy use in children has increased dramatically over the last three decades.[121]

Careful screening, assessment, and individual care planning for each patient constitute the foundation of effective treatment of mental and behavioral health challenges.[122] The safe administration of psychotropic medication to children requires medical oversight, treatment planning and health monitoring, before, during, and after the time period in which medications are used.[123] Oversight of children’s health enhances continuity of care, increases placement stability, decreases the incidence of adverse drug reactions and polypharmacy interactions, and can decrease the need for psychiatric hospitalization.[124]

Regular lab testing is a fundamental component of medical oversight.[125] Lab tests can reveal the effects a medication may be having on the body, including changes in hormones, weight, electrolytes, and organ function.[126] Because the risks of adverse side effects from psychotropic medication increase with polypharmacy, and polypharmacy can result in dangerous or deadly drug interactions, it is vital that physicians have current information about a patient’s medication regimen and treatment history.[127]

Chemical Restraint

Seroquel is an atypical antipsychotic approved by the FDA to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression.[128] After Seroquel’s initial FDA approvals, manufacturer AstraZeneca illegally marketed off-label use of the medication, targeting physicians who did not treat the conditions for which Seroquel was clinically approved.[129] Instead, AstraZeneca targeted marketing efforts at physicians who treat the elderly, primary care physicians, and adolescent and pediatric physicians in long-term care facilities, and in prisons.[130] The company, without clinical evidence, promoted Seroquel’s use in treating aggression, anger management, anxiety, insomnia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and other conditions.[131] In its marketing efforts, the company also engaged doctors to promote Seroquel, conduct studies on unapproved uses of Seroquel, and to serve as authors on studies promoting Seroquel in which the “authoring” doctors were not involved.[132]

Although declared illegal by the Unites States government,[133] Seroquel continues to be commonly prescribed for multiple off-label uses, including the treatment of insomnia.[134] In recent years, the medical community has grown increasingly concerned about the off-label prescription of antipsychotics, and Seroquel in particular, due to limited evidence supporting its off-label use and its potentially damaging side effects.[135]

Use of Seroquel as an emergency intervention indicates the use of the medication as a control rather than clinical measure, as the clinical benefits of Seroquel take weeks to months to be effective.[136] Facilities administer Seroquel to children to control their sleep patterns, their energy levels, or in response to specific behavioral incidents.

Disability Rights Tennessee (DRT), observed the practice of increasing children’s Seroquel dosage in an RF as an “emergency psychotropic intervention,” despite Seroquel’s lack of immediate impact.[137] In one facility, staff increased a child’s Seroquel dosage from 50 mg to 300 mg as an emergency intervention.[138]

Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC) has identified similar problematic uses of Seroquel by for-profit youth RFs. DRNC found in reviewing state records that staff had administered Seroquel numerous times to a child who did not have any diagnoses that would indicate use of antipsychotics. In this instance, the RF only administered Seroquel to the child while she was physically restrained, indicating the medication’s use as a chemical restraint rather than as treatment.[139] “As needed” prescriptions (often called in medical records as PRN for “pro re nata,” meaning “whenever necessary.”) can lead to a failure to properly document the administration of Seroquel and other such medications to children. For example, the same North Carolina facility was also cited for ordering multiple dosages (50mg and 150mg) of Seroquel on the same day without any documentation of the medication’s administration. In fact, the use of medication for the purposes of restraint and/or behavioral control is so ubiquitous that children and youth have a name for it: “Booty Juice.”[140]

In 2019, Oregon and Montana state agencies investigated Montana’s Acadia facility and uncovered significant and multiple incidents involving chemical restraint. Oregon has placed children at the facility.[141]

Behavior Management

For years, one facility in Alabama employed a practice called “Group Ignorance” (GI).[142] Group ignorance, in essence, is shunning—a practice sure to diminish a child’s sense of dignity and self-worth. According to the facility’s resident handbook,[143] girls on GI cannot “interact with peers and [are] required to remain 10 feet from all residents at all times.”[144] Girls are allowed to interact with peers only during participation in billable services such as basic living skills instruction and therapist-led group therapy.[145] Girls are not allowed to engage in “small talk” with staff, and even therapeutic discussions with staff “must be minimal—only enough to support/encourage the resident.”[146] While in the common area, girls must sit in a chair facing the wall.[147] Residents who interact with another girl on GI risk being placed on GI themselves.[148] Girls at that facility reported to ADAP that they had been on GI for months at a time.[149] One girl, with a history of self-harm, reported to ADAP staff that she attempted suicide in a facility bathroom as a result of her extreme emotional distress from being on GI.[150]

Many RFs also use convoluted point/level systems that residents must work their way through and complete before being eligible to leave.[151] Each youth accumulates points with good behavior, moving up levels that become progressively less restrictive, or loses points with behavioral violations, moving down levels that become more restrictive.[152] These systems are punitive in nature and facility staff often arbitrarily withhold or threaten to withhold points/treats/outings as a means of coercion and punishment.[153]