People with disabilities are in every community, and it is long overdue that federal data collection and calculations do not overlook or forget the disability community.

This report highlights the importance of accurate data, the availability of data on the disability community today, the limitations that exist and what needs to be improved in federal data collection moving forward. Both federal agencies and the disability community need to further engage and collaborate on the best practices on how to be fully inclusive of the disability community in the future to achieve real change.

Download “Count Everyone, Include Everyone” (PDF)

The National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) wishes to thank New Venture Fund for their financial support of this project to explore census results and disability representation in federal data surveys.

There would be no report without the time and input from Census Bureau staff, census experts, and disability rights advocates across the country.

This report was researched and written by Jennifer M. Koo and Erika M. Hudson of the National Disability Rights Network. Curtis L. Decker, Eric Buehlmann, Tina Pinedo, Kenneth Shiotani and David Card reviewed and edited the report. Production was coordinated by Tina Pinedo.

The National Disability Rights Network (NDRN) is the nonprofit membership organization for the federally mandated Protection and Advocacy (P&A) systems and the Client Assistance Programs (CAP) for individuals with disabilities. The P&As and CAPs were established by the United States Congress to protect the rights of people with disabilities and their families through providing legal support, advocacy, referral, and education. P&As and CAPs are in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. territories (American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and there is a P&A and CAP affiliated with the American Indian Consortium which includes the Hopi, Navajo, and San Juan Southern Paiute Nations in the Four Corners region of the Southwest.

As the national membership association for the P&A/CAP Network, NDRN has determinedly sought federal support for advocacy on behalf of people with disabilities and expanded P&A programs from a narrow initial focus on the institutional care provided to people with intellectual disabilities in facilities to include advocacy services for all people with disabilities no matter the type or nature of their disability and where they live. Collectively, the P&A and CAP Network is the largest provider of legally based advocacy services to people with disabilities in the United States.

P&As and CAPs work to improve the lives of people with disabilities by guarding against abuse; advocating for basic rights; and ensuring access and accountability in health care, education, employment, housing, transportation, voting, and within the juvenile and criminal justice systems.

Taking place once every ten years per the United States Constitution, the decennial census is an exciting opportunity for the federal government to conduct a nationwide population count and gather information about the country’s inhabitants that will inform public policy in the decade to come. The decennial census plays a dynamic role in developing America’s governmental bodies and guiding equitable representation for all. It helps stakeholders from all levels identify current and future needs for decisions surrounding healthcare, education, housing, transportation, food, and other services.

The U.S. Congress created and tasked the U.S. Census Bureau (within the U.S. Department of Commerce – DOC) with the esteemed responsibility of accounting for every person living in America. The data provided by the U.S. Census Bureau is necessary to implement and evaluate many civil rights laws and policies, and to ensure equal opportunities and access to all social and economic aspects of society.

Throughout history, people with disabilities have experienced disproportionate barriers to full participation in society. Even though people with disabilities belong to every single American demographic, they are seldom included or adequately represented in federal data and consequently receive inadequate support and funding.

Recognizing a pattern of historically low decennial census participation rates for people with disabilities, efforts by the U.S. Census Bureau, NDRN and the P&As, and other disability rights organizations have been taken to ensure a full and complete count for the 2020 Census, America’s most recent census. These efforts included improving outreach to the disability community and providing additional accessibility measures to assist in census completion. Though admirable, these efforts need to be consistently implemented and improved going forward to ensure full access and protection of the civil liberties of people with disabilities.

Beyond the decennial census, the U.S. Census Bureau tracks important federal data through conducting a variety of surveys including the American Community Survey (ACS), Current Population Survey (CPS), and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Although the breadth and depth of these surveys differ, they all offer meaningful insights about the American population, including economic insights as well as other relevant demographic information (e.g., racial, and ethnic prevalence). These surveys assist the decennial census in maintaining fair, and proportionate representation politically, economically, and socially. The ACS and SIPP are the two main surveys used to track various tabulations for the disability community, each asking about various specifications and aspects of disability as they relate to a variety of factors including employment, income, and much more.

There are other federal agencies that also track disability data including the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Social Security Administration (SSA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Department of Education (ED), Department of Justice (DOJ), and Department of Labor (DOL). These federal agencies spotlight data that – although not nearly as comprehensive as the decennial census – is unique to what the U.S. Census Bureau collects, covering topics such as educational disparities, detailed statistics on community living and independence, and information on crime.

Given the diverse nature of disability, and the many differing approaches to classifying disability across several federal agencies, there are certain limitations to the federal disability data that currently exists. These include difficulty accessing and navigating data, gaps in specific data tabulations (such as criminal justice, health care inequities, and racial disparities), and limited engagement from the disability community. Other limitations and recommendations for federal agencies and disability advocates alike are included in the latter sections of this report.

Moving forward, it is important to center and involve people with disabilities in all federal data collection and analysis processes. Improving access to representative and inclusive data is necessary to dismantle disability-based discrimination and further opportunities and protection for everyone, including people with disabilities.

Access to accurate, inclusive, and representative data is becoming increasingly important to the disability rights community. Although there has been an increase in efforts to include disability figures in federal data, more research exploring the diverse aspects of disability is needed to better support the various needs of stakeholders (people with disabilities and their families, P&A and CAP agencies, etc.) who use this information to protect the human rights and civil liberties of people with disabilities.

In this report, NDRN uses data analysis tools and research methods to discover how the disability community is represented in federal data and examines how federal agencies have included people with disabilities in data in the past.

Additionally, NDRN evaluates if there are any limitations to this process, explores alternative statistics and data sources, and identifies if there are any gaps that need to be filled or research objectives that should be further investigated in federal population data.

Furthermore, NDRN studies what questions related to disability are currently asked on U.S. Census Bureau surveys, and explores what promotions, supports, accommodations, and measures for accessibility were offered to the public based on research gathered from public resources and informational interviews conducted with the Census Bureau, other federal agencies that track disability tabulations, the P&A systems, and other disability rights organizations.

AAA – Area Agencies on Aging

ACL – Administration on Community Living

ACS – American Community Survey

ADA – Americans with Disabilities Act

AGID – AGing, Independence, and Disability

ALH – Assisted Living Homes

ASEC – Annual Social and Economic Supplement

BIPOC – Black, Indigenous, and People of Color

BJS – Bureau of Justice Statistics

BLS – Bureau of Labor Statistics

BRFSS – Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System

CAP – Client Assistance Programs

CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CPS – Current Population Survey

DHDS – Disability and Health Data System

DLC – Disability Law Center

DOC – Department of Commerce

DOJ – Department of Justice

DOL – Department of Labor

DOQ – Data, Outcomes, and Quality

DRC – Disability Rights California

DREDF – Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund

ED – Department of Education

GQ – Group Quarter

HHS – Department of Health and Human Services

HTC – Hard to Count

IES – Institute of Education Sciences

NAC – National Advisory Committee

NCES – National Center for Education Statistics

NDRN – National Disability Rights Network

NIMH – National Institute of Mental Health

NRFU – Nonresponse Followup

NSDUH – National Survey on Drug Use and Health

OAA – Older Americans Act

ODEP – Office of Disability Employment Policy

ORDP – Office of Retirement and Disability Policy

OSERS – Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services

P&As – Protection and Advocacy Systems

RSA – Rehabilitation Services Administration

SAMHSA – Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration

SILC – Statewide Independent Living Council

SIPP – Survey of Income and Program Participation

SNAP – Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

SSA – Social Security Administration

SSDI – Social Security Disability Insurance

SSI – Supplemental Security Income

SUA – State Union on Aging

TTY – Teleprinter or Teletypewriter

WHO – World Health Organization

Existing Disability Population Statistics

Despite the fact that approximately 15 percent (one billion) of the world’s population[i] and 26 percent (61 million) of adults in the United States live with a disability[ii], individuals with disabilities are often excluded from important data collection opportunities, including the decennial census. Beyond social and structural barriers to participation, there are a plethora of considerations that may account for these disparities. This lack of participation has consequences – without proper representation, people with disabilities are vulnerable to adverse socioeconomic outcomes, including lower education and employment rates, poorer health outcomes, and increased poverty rates.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in America disability is especially prevalent in older adults, women, and racial and ethnic minority groups. Age plays a significant role in determining the likelihood of someone having a disability. In 2015, statistics showed that people ages 35 to 64 made up the largest age demographic (16 million) of Americans with disabilities, while 2 in 5 adults ages 65 and older are reported to have a disability. It has also been reported that 1 in 4 adult women have a disability.[iii]

The Pew Charitable Trust, an independent non-profit dedicated to improving public policy, informing the public, and invigorating civic life, states that the racial and ethnic backgrounds of people with disabilities varies greatly. According to the report, American Indians or Alaskan Natives were most likely to report having a disability at 17.7 percent. Black and white Americans were about equally as likely to report having a disability, at 14.1 percent and 13.9 percent respectively. Of the tracked groups, Asian Americans were the least likely to report having a disability at 6.9 percent.[iv]

Importance of Federal Data to the Disability Community

While demographic data indicates that some groups are more likely to have higher disability rates than others, disability data should be considered its own category. Even though people with disabilities are a part of every community in the country, the disability community is often underrepresented in and excluded from population data, and consequently experience disproportionate barriers to resources (including health care, transportation, housing, social programming support, etc.).[v] The U.S. Census Bureau has identified the disability community as a hard-to-count (HTC) population, meaning that the disability community is at a greater risk of being undercounted and misrepresented in federal data.[vi] Inclusive data that accurately includes and accounts for people with disabilities is important to dismantle disability-based discrimination and advance opportunities and protections so that everyone can fully participate in society without barriers to flourishing.

The U.S. Census Bureau has taken impressive measures to include people with disabilities and make participation in federal surveys (including the decennial census and ACS) more accessible.[vii] This is important because the data gleaned from these federal surveys serve as a foundation for fair political, social-cultural, and economic representation of people with disabilities. Securing a fair and accurate census count is essential for the appropriate distribution of federal funding given this data tells us how many people are eligible for certain programs. The data from these surveys determines Congressional districts, influences how nearly $700 billion in federal funding is distributed, and establishes where legislative, school, and voting boundaries are set.[viii] Some of the programs that rely on census data for federal funding include the P&A and CAP programs, Education Grants, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, Housing (Section 811), Statewide Independent Living Councils (SILCs), Employment (Vocational Rehabilitation Programs), transportation, and more.[ix]

Disability is everywhere and is a part of every community. As such, it is vital that everyone participates in and conducts effective outreach for federal surveys to protect and advance the rights of people with disabilities. Moving forward, it will become increasingly important for the Census Bureau and partners to take even further accessibility measures to better include people with disabilities in decennial and other population surveys such as the American Community Survey (ACS), which features disability data.

Federal Agencies and Disability Data: What does the federal government collect on disability?

While disability related questions are typically not included in large-scale federal surveys (such as the decennial census), the federal government does collect information that is meaningful to people with disabilities and their families.

The U.S. Census Bureau is a Bureau/Office under the Department of Commerce (DOC) with the mission to serve as the nation’s leading provider of quality data about its people and economy. Beyond the U.S. Census Bureau, there are also other federal agencies that collect disability data, which are important to consider as we track disability data points and investigate opportunities for more accessible and accurate data collection.

[i] https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability#1

[ii] https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

[iii] https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

[iv] https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/07/27/7-facts-about-americans-with-disabilities/

[v] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4355692/

[vi] https://censuscounts.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/People-with-Disabilities-Brief.pdf

[vii] https://www.census.gov/about/policies/section-508.html

[viii] https://www.census.gov/about/what.html

[ix] https://www.ndrn.org/resource/why-the-census-matters-for-people-with-disabilities-a-guide-to-the-2020-census-operations-challenges/

History

As mandated in Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, a total population count is required every ten years. Since the launch of the first census in 1790, the need for accurate and representative information regarding the U.S. population became increasingly important.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the decennial census (i.e., a population count recurring every ten years) gradually expanded to encompass hundreds of topics pertaining to America’s demographic, agricultural, and economic information. Realizing the growing breadth and depth of the decennial census, Congress passed legislation that created a permanent Census Office within the Department of the Interior on March 6, 1902. In 1903, the Census Office was transferred to the Department of Commerce and Labor, officially joining the Department of Commerce (DOC) when the Department of Commerce and Labor split into two separate departments in 1913.[i]

As a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, the U.S. Census Bureau is responsible for collecting and producing data about people living in America. The agency’s primary mission is to conduct a total population count every ten years via the decennial census Additionally, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts over 130 surveys and programs a year, such as the American Community Survey (ACS), U.S. Economic Survey, and Current Population Survey (CPS).[ii]

Decennial Census

What is the decennial census?

Taking place every ten years, the decennial census, also known as the Population and Housing Census, is set to count every resident in the United States of America.[iii] Because the decennial census is the largest operation conducted in the nation, the U.S. Census Bureau conducts extensive research, planning, and development in the years leading up to each decennial census. For the 2020 Census, the U.S. Census Bureau focused their efforts on increasing self-response rates via encouraging Internet participation and adopting measures to decrease census-taker workload and increase productivity.[iv]

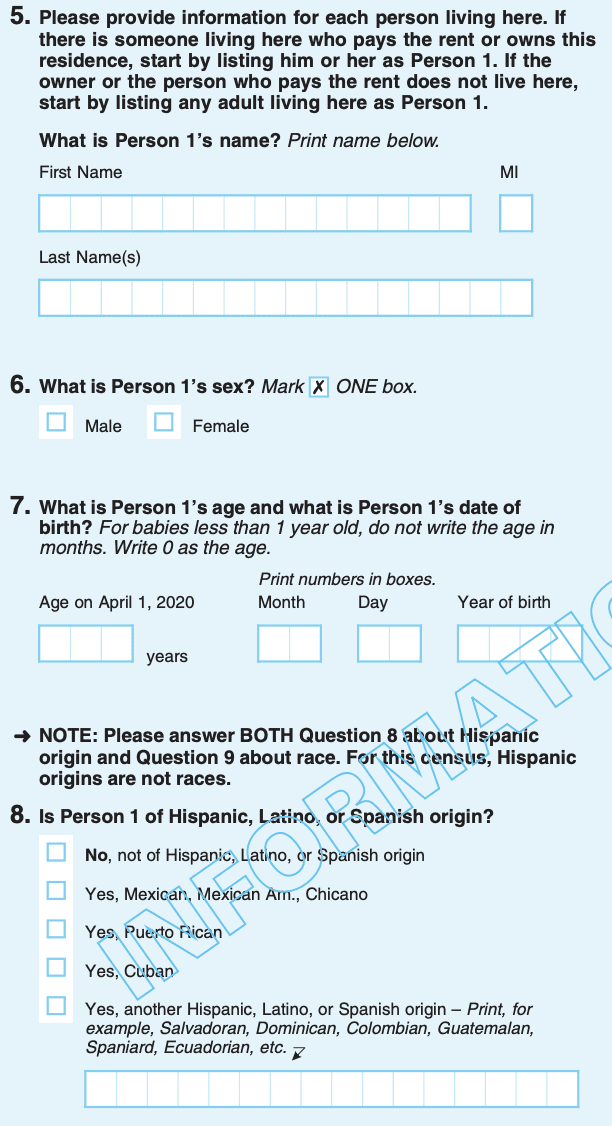

A decennial census only needs to be completed by one person per household. The questionnaire asked questions pertaining to name, age, sex, race.

Screenshot of a sample 2020 Census questionnaire

Although there are not any specific questions related to disability in the decennial census, it is vital that people with disabilities respond to the survey to ensure they are represented in federal datasets for the next decade. The data collected determines Congressional districts, how federal funds are distributed, where legislative, school, transportation, and voting boundaries are set, and provides meaningful insights on who makes up our population (i.e., demographic information) and where we are going as a nation. There is a clear need for extracting meaningful findings concerning people with disabilities from population data, including the decennial census, American Community Survey (ACS), and other federal datasets.

NDRN, Protection & Advocacy Systems and the 2020 Census

The 2020 Census, America’s most recent decennial census, was one of a kind. It endured a global pandemic, numerous natural disasters and emergencies, and an ever-polarized American political climate. Despite all of this, U.S. Census Bureau staff, advocates, and the public, stepped up and advocated for a fair and accurate census that represented every community in America.

During the decade leading up to the count, civil rights organizations, community leaders, U.S. Census Bureau staff, grassroot organizations, and census advocates tirelessly worked to ensure an equitable decennial count. Decisions had to be made, questions had to be set, court battles were fought (and still are), and America was well on its way to start the once in a decade population count in order to set the stage for the next ten years. Yet, little engagement had been made to include people with disabilities.

Many individuals working to ensure an accurate and fair count were under the impression that many members of the disability community were going to be counted throughout the Group Quarter (GQ) enumeration process, and therefore required little engagement from census advocates. This misconception, led local, state, and national disability organizations, including NDRN, to spring into action as individuals with disabilities are a part of every community and represent a large part of the U.S. population from across the country, not just those in group quarter living situations, and needed to be included in all 2020 Census-related discussions and plans to ensure a fair, accurate, and accessible decennial count.

Throughout 2019 and in the early months of 2020 before the official count, NDRN worked closely with the U.S. Census Bureau and disability and civil rights partners to ensure that everyone was included in the 2020 Census discussions and plans. This work included collaborating on accessible materials, such as Braille and large-print forms, accessible web portals; researching and publishing information and material relevant to the disability community; conducting social media campaigns; and advocating for people with disabilities to have a voice in a fair, accurate, and accessible 2020 Census. NDRN also hosted (in-person and virtual) events and webinars about the importance of the disability community engaging and participating in national census surveys.

NDRN’s member organizations, P&A agencies, across the country also worked diligently in their state to ensure a fair, accurate and accessible count and learned first-hand how certain assumptions about people with disabilities and operational challenges impacted the 2020 Census count. For instance, Alaska’s P&A, Disability Law Center (DLC) of Alaska, alerted U.S. Census Bureau officials that outdated 2010 data was being used to count people living in Assisted Living Homes (ALHs) in the state. DLC helped the U.S. Census Bureau update the information and made sure the missing ALHs received the GQ enumeration packet in time to be counted. If it were not for DLC, hundreds of people in Alaska could have been missed in the 2020 Census emphasizing the need to collaborate with local organizations to ensure people are not missed or undercounted in the 2020 Census.

2020 Census Results

Timeline

After several years of preparation, the 2020 Census count officially launched in Toksook Bay, Alaska on Tuesday, January 21, 2020, to ensure that people living in remote areas were accurately represented in the process.[v]

Despite the hardships that accompanied 2020 – including the COVID-19 global pandemic, natural disasters, civil unrest, etc. – the U.S. Census Bureau and partners worked tirelessly to ensure a fair and accurate count. Even with the challenges, Census takers strived to be as flexible, practical, and persistent as possible to ensure the best results. According to the 2020 Census Apportionment Data Release, the 2020 Census represented the largest participation movement ever witnessed in our country.[vi]

For the first time in all of census history, participants had the option to answer the census online or by phone, in addition to the traditional method of submitting their census survey form via mail. Starting March 12, 2020, the public was invited to respond to the survey at my2020census.gov and by phone and mail. The survey was offered in American Sign Language and 46 other non-English languages and included more accessibility options (including Braille and large print Census completion guides).[vii] By October 16, 2020, 99.9% of household addresses nationwide had been accounted for in the 2020 Census. Approximately 67.0% of survey responses were completed through self-response online, by phone, or by mail (higher than the self-response rate of 2010), and 32.9% were accounted for through the Nonresponse Followup (NRFU) operation, the final 2020 Census data collection operation to count households that had not yet responded to the survey.[viii] If a household did not respond after one or more census taker visits, the census takers used high-quality administrative records (when available) to count people who did not self-respond to the 2020 Census. High quality records include alternative data sources such as tax, Medicare and Medicaid records, Social Security Administration (SSA) information, and 2010 Census data which census takers checked against these alternative data sources to see if they provided the same information for that address.[ix] If all of that didn’t work, they attempted to get information from a neighbor.

Even though the count has ceased, the data from the 2020 Census will affect communities across the country over the next decade. The count was just the beginning.

Apportionment Release

The United States experienced the second slowest population growth (an increase of 7.4% between the years 2010-2020) in U.S. history, with a total population count of 331,449,281 for the year 2020. States with the largest population count (between 10 and 40 million) include California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, and Michigan. States with the smallest population count (between 0.5 million and 1.4 million) include Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Delaware, Montana, Rhode Island, Maine, and New Hampshire.[x]

At the 2020 Apportionment Data Release Conference, it was revealed that while 37 states will keep the same number of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, 6 states will gain seats, and seven states will each lose one seat.[xi] This is especially important to people with disabilities as changes in congressional seating impact the social, economic, and political representation of the disability community, influencing the federal programming and support they might receive or lose.[xii]

Redistricting Data Release

Populations are constantly changing. It’s important that an area’s legislative bodies – Members of Congress, state legislators, county, and municipal officials – accurately represent that area. Redistricting is the act of organizing an area into new and appropriate political districts. It affects political power (i.e., who calls the shots, what issues a legislature will address/ignore, and which parties have the upper hand in government), and whether diverse communities are properly represented.

On August 12, 2021, the U.S. Census Bureau released a “legacy format” redistricting toolkit containing detailed data informing state and local governments on how to redraw electoral boundaries. A more user-friendly format of this same data was released in late September 2021. Stakeholders can use this information to evaluate local demographic data and compare it with their own sample-based surveys to see if the results align with their demographic projections (location, size, and characteristics of their local communities).[xiii]

The redistricting data release offers a preliminary snapshot of demographic trends and information of the nation by state, county, and city. Some of the characteristics include race and ethnicity, population 18 years and older, occupied, and vacant housing units, people living in group quarters such as nursing homes, prisons, military barracks, and college dormitories.

What to Look for Next

NDRN looks forward to exploring the upcoming 2020 Census data release which will include important population demographic information, such as statistics on age, sex, and race and ethnicity. Recognizing that disability is a natural part of life and is a part of every single community, NDRN values the importance of this information.

Once the data are released, the U.S. Census Bureau will continue quality checks to ensure the accuracy and quality of data collection and processing. The 2020 Census can be evaluated through comparing the results to other population totals and checking to see how well the process of conducting the census worked. Census workers are currently conducting Post-Enumeration Surveys[xiv] with preliminary results expected to be released in November 2021, as well as Demographic Analysis Surveys[xv] which will compare census results to other ways of measuring the population.

American Community Survey

Background

The American Community Survey (ACS) is an ongoing survey that provides information about the United States and its people, through generating data that – along with the decennial census – helps determine how nearly $700 billion in federal and state funds are managed on a yearly basis. The data collected provides public planners, officials, and entrepreneurs with yearly insights on jobs and occupations, educational attainment, veteran status, whether people own or rent their homes, and other social, housing, economic, and demographic topics including disability status. The latest data release also displays 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year estimates for the nation, which can be used accordingly for analyzing trends across various population sizes.[xvi]

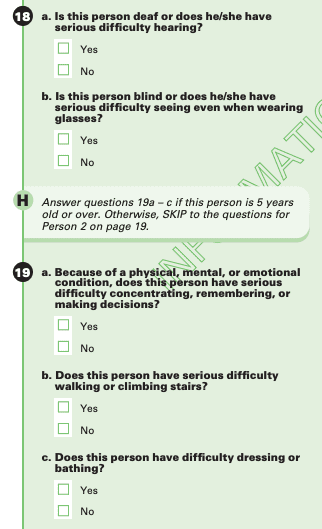

Screenshot of a sample ACS questionnaire

The ACS inquiries about six aspects of disability including hearing, vision, cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, and independent living). This information is especially helpful because it can measure overall disability numbers and be used to identify populations with specific aspects of disability.

What is the difference between the American Community Survey and the decennial census?

While both the ACS and the decennial census provide local and national leaders with essential programming and planning information, they are different. The ACS tells us how we live – providing information on our education, housing, jobs, and more – to provide insights on the social and economic needs of our communities each year. The decennial census is conducted every ten years, and provides an official population count for Congress.[xvii]

The ACS is conducted every month, every year, whereas the decennial census is conducted every ten years. The ACS is much smaller in scale and is sent to a sample of addresses (approximately 3.5 million per year) in the 50 states, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.[xviii] The decennial census, on the other hand counts every living person in the 50 states, District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the four U.S. territories. The scope of questions asked also differs between these two surveys. The ACS is more thorough, asking about topics not included on the decennial census, including education, employment, internet access, and transportation. “The ACS can provide more up-to-date information on hospitals and schools, insights on how to best support school lunch programs, improve emergency services, build bridges, and inform businesses looking to add jobs and expand to new markets, and much more.” The decennial census, on the other hand, asks a much smaller range of questions, such as age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, and owner/renter status. The ACS also provides information to communities and local and national leaders every year regarding economic development, emergency management, and understanding local conditions and issues. The decennial census provides an official count to the population and provides essential information that lawmakers can use to provide daily services and support for communities.[xix]

It is important to fill out both the ACS and decennial census because both surveys help communities develop the most effective plans for the future.

Current Population Survey

The Current Population Survey (CPS) is an initiative sponsored jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau, and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The Current Population Survey is the leading source of labor force population data in the United States.

The questionnaire for the labor force portion of the CPS interview is computerized and consists of more than 200 questions. It is administered by U.S. Census Bureau field representatives across the country through in person and telephone interviews, as well as at the U.S. Census Bureau’s two centralized collection facilities located in Jeffersonville, Indiana and Tucson, Arizona. The questionnaire abides by a complex skip system using the responses to several questions to ensure that respondents are only asked a small set of questions about themselves, on average taking participants about 6 minutes to complete.[xx]

The U.S. Census Bureau uses a probability selected sample of about 60,000 occupied households to administer the survey to. Individuals must be 15 years of age or over and not in the Armed Forces to meet eligibility requirements. Due to child labor laws, the BLS typically publishes labor force data that is only applicable to people aged 16 and older. Unfortunately, people in institutions, such as prisons, long-term care hospitals, and nursing homes are ineligible to be interviewed in the CPS, which could exclude a significant number of people with disabilities.[xxi]

Beyond surveying for labor force information, the CPS also includes additional questions that address other areas of interest – such as annual work activity and income, veteran status, school enrollment, worker displacement – for labor market analysts. In addition, because the survey has a large sample size and covers a broad range of participants, the CPS supplements are often used to collect data on topics that don’t fall directly within the traditional realm of what one might expect regarding labor force information, including expectation of family size, tobacco use, computer use, and voting patterns.[xxii]

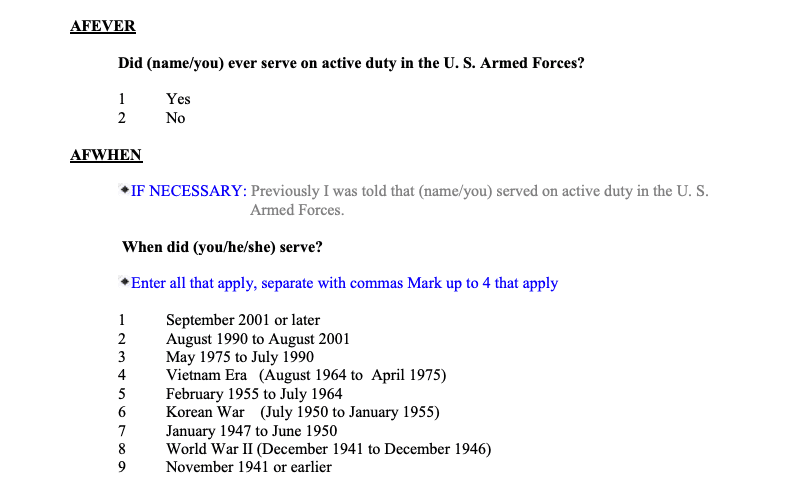

Screenshot of CPS interview questions

Like the ACS, the CPS collects information on various aspects of disability including hearing difficulty, vision difficulty, cognitive difficulty, ambulatory difficulty, self-care difficulty, and independent living difficulty.

The CPS also conducts an Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) which asks additional questions that provide information on disabilities impacting employment or work. The U.S. Census Bureau disclaims that the questions of the CPS ASEC were not designed to measure disability specifically, but “rather, the questions were intended to measure labor force status or capture certain income sources.”[xxiii] They strongly recommend that individuals who are interested in using CPS ASEC to measure work disability to take caution and consider the Uses and Limitations of CPS Data on Work Disability when using this data source.

Survey of Income and Program Participation

The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) is a household-based survey that provides information for income and program participation, through collecting data and gauging change for many important datapoints including economic well-being, family dynamics, education, assets, health insurance, childcare, and food security. SIPP is a longitudinal study, designed as a continuous series of national panels, with each panel reflecting a nationally representative sample interviewed over a multi-year period lasting for about three to five years.[xxiv]

Like the ACS, decennial census, and CPS, SIPP provides data on a broad range of topics. SIPP is unique in that it allows for the integration and evaluation of information for separate topics to form a single, unified database. Since its establishment in 1983, SIPP has been able to provide meaningful insights on America’s economic well-being and changes to our nation’s economics over time. SIPP data can examine several demographic characteristics that exist within the interactions between tax, transfer, and other government and private sector policies to evaluate the distribution of income and the success of government assistance programs.[xxv]

SIPP data is also used to evaluate the effectiveness of federal, state, and local government programs through providing a nationally representative sample for “evaluating annual and sub-annual income dynamics, movements into and out of government transfer programs, family and social context of individuals and households, and interactions among these items. A major use of the SIPP has been to evaluate the use of and eligibility for government programs and to analyze the impacts of options for modifying them.”[xxvi]

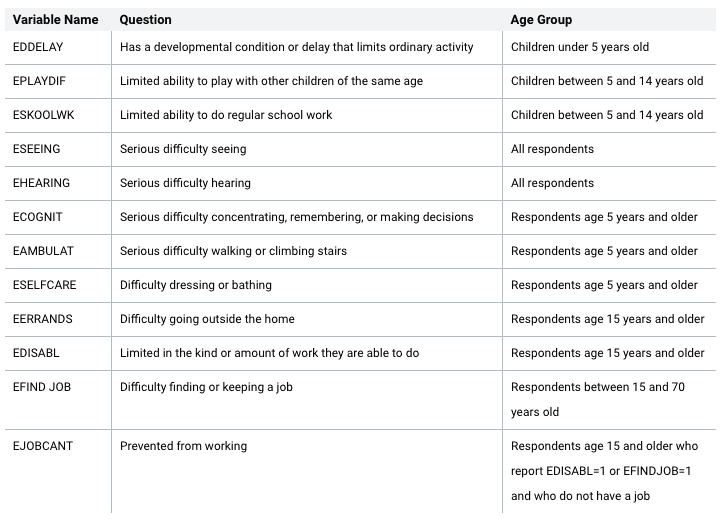

Questions used to measure disability in the 2014 SIPP

While SIPP’s disability measures cover a broad range of activities (such as use of assistive aids, difficulty working at a job or business, and limitations in functional activities), SIPP is limited as a data source due to the small sample size of the survey. Because of the range of definitions federal agencies use to classify disability status, researchers should make note of SIPP’s classifying characteristics to ensure that this survey best suits their research needs.

How to Navigate Data

In addition to having access to federal statistics, many stakeholders – primarily disability rights advocates – may benefit from getting information at the municipal and regional levels. For example, acquiring information about the number of people with mobility disabilities in a specific geographic area can be helpful in providing advocates with the necessary information to convince their representatives to allocate adequate funding towards accessible public transportation and housing.[xxvii]

As of January 1, 2013, the U.S. Census Bureau currently has six active regional offices that are responsible for geographically specific data collection and dissemination. These offices serve as the primary point of contact for local media and organizations. Through conducting continuous surveys and engaging regularly in field research, the Regional Offices offer up-to-date statistics on people, places, and the economy. Interested stakeholders can contact their regional offices with specific queries. Appropriate Regional Office contact information can be found on the U.S. Census Bureau’s website.[xxviii]

[i] https://www.census.gov/history/www/census_then_now/

[ii] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/surveyhelp/list-of-surveys/household-surveys.html

[iii] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/censuses.html

[iv] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/about.html

[v] https://www.census.gov/library/video/2021/a-look-back-at-the-2020-census.html

[vi] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2021/2020-census-apportionment-counts.html

[vii] https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/factsheets/2019/dec/2020-accessible-everyone.pdf

[viii] https://www.census.gov/library/video/2021/a-look-back-at-the-2020-census.html

[ix] https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/planning-docs/administrative-data-used-in-the-2020-census.pdf

[x] https://www.census.gov/library/video/2021/what-is-apportionment.html

[xi] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2021/2020-census-apportionment-counts.html

[xii] http://www.georgetownpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/GCPI-ESOI-NDRN-Why-the-Census-Matters-for-People-with-Disabilities-Large-Print-20190822.pdf

[xiii] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/2020/planning-management/release/redistricting-data-product-faqs.html

[xiv] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/pes.html

[xv] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/2020-demographic-analysis-estimates.html

[xvi] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/guidance/estimates.html

[xvii] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about/acs-and-census.html

[xviii] https://www.census.gov/acs/www/methodology/sample-size-and-data-quality/sample-size/

[xix] https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/programs-surveys/acs/about/ACS-54(HU)(3-2020).pdf

[xx] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/methodology/collecting-data.html

[xxi] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/technical-documentation/methodology.html

[xxii] https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/methodology/CPS-Tech-Paper-77.pdf

[xxiii] https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-cps.html

[xxiv] https://data.nber.org/sipp/docs/2014-SIPP-Panel-Users-Guide.pdf

[xxv] https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sipp/about/sipp-introduction-history.html

[xxvi] https://data.nber.org/sipp/docs/2014-SIPP-Panel-Users-Guide.pdf

Beyond the decennial census and other U.S. Census Bureau surveys, disability researchers, advocates, and communities can look to other federal agencies to find information that may better suit their needs.

Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Community Living

Regardless of age or disability, all people deserve to have their right to self-determination protected. Whether it’s about selecting a place to live or choosing fulfilling work opportunities, The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration on Community Living (ACL) believes that every person should have the self-agency to make informed choices about important decisions in their lives. [i]

ACL maintains an online query system based on ACL-related data and surveys, a system coined The AGing, Independence, and Disability (AGID) Program Data Portal. The goal of AGID is to provide a single, user-friendly source detailing information on ACL support and care services for older populations and their caregivers, and people with disabilities of all ages. AGID also includes important population characteristics from the Older Americans Act (OAA) services and ACL Special Tabulations from the Census Bureau.

Designed to provide different data aggregations, AGID offers four paths:

- Data-at-a-Glance – Individual Data Profiles

This path allows users to access individual data elements within AGID’s state-level databases. It is an especially powerful tool that can be used to produce quick tables and geographical representations of data elements. - State Profiles – State-Level Summaries

State profiles allow an individual to navigate state-level data elements from OAA Programs for the selected state, as well as draw distinctions among specific states and the total nation. The location of the State Unit on Aging (SUA), Area Agencies on Aging (AAA), and Tribal Organizations are also presented in map and tabular formats.

- Custom Tables – Multi-Year Tables

Under this path, users can select data elements that are applicable to their needs and have options to refine their results based on demographic stratifiers and geographic locations that are meaningful to their search. Users may also analyze trends across time and geography by selecting multiple years of data or multiple geographic locations.

- Data Files – Full Database Access

This path provides full access to ACL survey databases and other ACL Special Tabulations conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Department of Education, Rehabilitation Services Administration

Understanding the diversity of challenges that individuals with disabilities and their families face, the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) seeks to maximize employment opportunities, independence, and enhanced integration into the community for the disability community. RSA does this through assisting states and other agencies in providing leadership, resources, vocational rehabilitation, and other services to individuals with disabilities.

Operating under the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS) within the U.S. Department of Education (ED), one of the goals of the Rehabilitation Services Administration is to support the OSERS vision to raise outcomes and expectations for all people with disabilities.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), an initiative within the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES), is the primary federal resource for collecting and analyzing national and global education data. NCES was established to fulfill a Congressional mandate to collect, analyze, and publish statistics reflecting the condition of American and international education. This resource is increasingly important for the disability community, as the data can provide meaningful insights on disability-related educational disparities and provide suggestions to dismantle these disparities.

Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division

The enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 created the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ) to uphold the civil and constitutional rights of all Americans. The Division enforces federal statutes prohibiting discrimination because of race, color, sex, disability, religion, familial status, national origin, and citizenship status. The Division’s work is coordinated through 11 primary sections: Appellate, Criminal, Disability Rights, Educational Opportunities, Employment Litigation, Federal Coordination and Compliance, Housing and Civil Enforcement, Immigrant and Employee Rights, Policy and Strategy, Special Litigation, and Voting.[ii]

As the primary statistical agency of DOJ, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) – established in 1979 – serves as the nation’s primary source for criminal justice statistics. The mission of BJS is to “collect, analyze, publish, and disseminate information on crime, criminal offenders, victims of crime, and the operation of justice systems at all levels of government. BJS also provides financial and technical support to state, local, and tribal governments to improve both their statistical capabilities and the quality and utility of their criminal history records.”[iii]

Data exploring the intersection between disability and the criminal justice system is limited. Further research, and increased access to public services (e.g., provision of education and health care while in prison, etc.) are essential to better protect the rights of people with disabilities within the criminal justice system.

Department of Labor, Office of Disability Employment Policy

As the only non-regulatory federal agency that promotes policies to increase workplace success for people with disabilities across all sectors and levels of government, the Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP)’s mission is to increase the quantity and quality of employment opportunities for people with disabilities. Some of the services that ODEP provides include a toolkit for individuals with disabilities on securing financial future[iv] and COVID-19 and Long-COVID-19 resources[v], which includes guides on how to request accommodations, navigate employee benefits, financial security, and more.

Additionally, prior to being incorporated into the Department of Labor in 1903, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) was located within the Department of Commerce and Labor in 1903 alongside the U.S. Census Bureau (which transferred to the Department of Commerce in 1913). BLS serves as the nation’s primary fact-finding agency covering a vast field of labor economics and statistics, and plays an instrumental role in collecting, processing, analyzing, and disseminating essential information to the public, U.S. Congress, and other multi-level agencies.[vi]

BLS works collaboratively with the U.S. Census Bureau to highlight disability data and glean meaningful information on the nation’s labor force in the Current Population Survey.

Social Security Administration Disability Program

The Social Security Administration (SSA) has a long history of collecting and disseminating data about people, including their identifying information, their employers, their addresses, and more. The Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) programs are resources run by the SSA that aid people with disabilities. The SSDI program pays benefits to insured (i.e., taxpaying) individuals with disabilities and their family members. The SSI program provides benefits to adults and children with disabilities with limited income.[vii]

The SSA has numerous datasets available:

- Social Security Data Page

Because of Privacy Laws, the Internal Revenue code, and other statutes, most of the data has restricted public access, but full listings of what is collected are listed. Some of the data that has been anonymized is fully accessible by the public. - Social Security Administration (SSA) Open Government Select Datasets

These datasets include information regarding disability program and processing data as well as information about the numbers behind applications filed. - Selected Data from Social Security’s Disability Program

This table reflects disabled worker beneficiary statistics by calendar year, quarter, and month. - Research, Statistics, & Policy Analysis

These annual statistic reports are a collaborative effort among Office of Research Demonstration, and Employment Support, and the Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, and the Office of Retirement and Disability Policy (ORDP).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The mission of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is to “protect America from health, safety and security threats, both foreign in the U.S.” through fighting diseases and equipping citizens with public health resources. The CDC increases our nation’s health security through prioritizing scientific research and disseminating health information that will help protect our nation from health threats and responding to health crises.[viii]

The CDC’s Disability and Health Data System (DHDS) provides public access to state-level and demographic data about adults with disabilities. To improve public health communications and results with the disability community, the CDC has created helpful resources such as the Beginner’s Guide to Disability and Health Data System and Disability and Health Data System: Beyond the Basics tutorials which teaches users to identify health barriers that adults with disabilities may experience. DHDS includes Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) data, and covers six functional types of disability (cognitive, hearing, mobility, vision, self-care, and independent living). Researchers seeking specific information can contact [email protected] over e-mail with any questions.

Additional resources relating to disability that the CDC offers include:

- CDC: Disability Impacts All of Us

- Arthritis Data and Statistics

- Diabetes Statistics

- Behavioral Risk Factors Data Portal

- CDC National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

Federal Resources that Provide Accessible Data on Mental Health and Disabilities

Mental illnesses are common in the United States, affecting tens of millions of people each year.[ix] Estimates suggest that only half of people with mental illnesses receive treatment.[x] The following federal agencies and surveys spotlight various tabulations and currently available statistics on the prevalence and treatment of mental illnesses among the U.S. population:

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

- SAMHSA Data, Outcomes, and Quality (DOQ)

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

NSDUH provides estimates of substance use and mental illness at national, state, and substate levels.

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

[i] https://acl.gov/about-community-living

[ii] https://www.justice.gov/crt

[iii] https://bjs.ojp.gov/bjs-data-quality-guidelines/overview

[iv] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ebsa/secure-your-financial-future

[v] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/odep/topics/coronavirus-covid-19-long-covid

[vi] https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/dolorigabridge

[vii] https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/disability/

[viii] https://www.cdc.gov/about/organization/mission.htm

Inaccessible Data

When searching for federal disability data, researchers generally find the most information through looking at three U.S. Census Bureau surveys: the American Community Survey (ACS), the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), and the Current Population Survey (CPS). Each of these surveys ask about six different aspects of disability (seeing, hearing, mobility, self-care, independent living, and cognitive issues) and are designed to produce reliable statistics about people with disability.

Because the primary focus of these surveys is to provide detailed information about our nation to all our communities, those who are specifically interested in disability tabulations might not necessarily have the knowledge on how to access the right information and use what is presented.

Take the 2020 Census, for example, it offered various ways of responding. However, this too can improve. For instance, the TTY (Teleprinter or Teletypewriter) technology advertised for respondents to participate by phone was helpful to some who still rely on this type of technology, but to most, this technology is outdated, as now individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing now prefer video relay systems instead.

Further, in 2020 the Census Bureau also provided braille and large-print language guides to individuals who wanted to respond by mail, which they heavily advertised when speaking to disability organizations prior to the count to showcase the inclusion and access they were offering, yet they did not provide the necessary information on how to eventually access the braille guide if needed. Additionally, they did not provide those who were blind or low vision with the option to respond to the 2020 Census by mail given the guide itself was not the form, and respondents were expected to either complete the standard form by mail (which could be difficult for someone who is blind or low vision) or respond online or by phone.

Limited Engagement from Disability Community

Despite making up nearly a quarter of the American population, people with disabilities are considered one of the most under-counted populations. This is problematic because without proper federal funding and political representation, people with disabilities are at risk of losing their civil liberties and protections. In 2019 prior to the most recent decennial census, Disability Rights California (DRC) and the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) issued the 2020 Census Disability Community Toolkit, which included responses from individuals with disabilities as to why they do not participate in the census. Responses included “I’ve never been asked,” “I don’t think the census has an impact on my life,” and “I’m worried information will be used against me” (participants were concerned that personal information provided to the census could interfere with Social Security, Medical and other benefit procurement).[i]

DRC and DREDF found during their 2018 study that out of the 68 people they interviewed, only 11 people had received the census in the past. DRC and DREDF concluded that “the number of people with disabilities who have participated in the census is significantly lower than the number of people with disabilities who should and could be counted.”[ii]

As the disability community continues to face inequities, many researchers have begun to question why the decennial census does not include any disability-specific questions. Because the decennial census does not include disability-related questions, people with disabilities do not believe that the Census will have an impact on their life.[iii] Still, because the decennial census is intended to provide a snapshot of the entire population and has implications on every aspect of life, it’s important to make every effort to count and include everyone, especially people with disabilities. Disability data helps provide adequate housing, health care, aid, and assurance of equal opportunity. In addition, it informs researchers, policymakers, and advocacy groups on whether people with disabilities have access to the same opportunities as people without disabilities.[iv] A lack of communication about the importance of completing the census has dire consequences on the disability community because it creates opportunities for underreporting and will overarchingly hurt people with disabilities by not providing them with the necessary resources for their self-determination and flourishing.[v]

Another reason why the disability community might reflect limited engagement is because they experience barriers to completing the surveys due to inaccessibility issues. Here are some of the measures the U.S. Census Bureau took to encourage people with disabilities to participate in federal data surveys:

- The U.S. Census Bureau produced a resource demonstrating how to respond to the American Community Survey.

- 5 million addresses across the country are asked to participate.

- Responding onlineis unfortunately not an option for people living in Puerto Rico, people living in group housing (this could include people with disabilities), or people living in homes where the U.S. Census Bureau has an incomplete mailing address.

- Other ways to respondinclude over mail, phone, or in-person interviews. Participants may also call their Census Regional Office if they want to verify if their in-person interviews are legitimate.

- The U.S. Census Bureau highlighted various accessibility options for completing the 2020 Census.

- To encourage participation, the U.S. Census Bureau sent out messaging insinuating that “it’s easy for you to be counted,” and providing information about the accessibility measures (for a wide range of disabilities) offered to assist in completing the questionnaire.

Additionally, disability organizations in recent years have become more engaged with federal data as they are reliant on the data itself in their own work of advocacy, policy making and support services to people with disabilities. Further, the 2020 Census resulted in disability organizations engaging with both the U.S. Census Bureau and the community to ensure people with disabilities were not missed in the most recent census given the Bureau considered the community a “hard to count” population.

In summary, the U.S. Census Bureau provided many resources[vi] on the importance of completing their surveys but did not have enough information on accessibility in wholly accessible formats.[vii] To make the most of their promotions, it would be helpful for federal agencies that hope to connect with the disability community to implement universal design.

It is also important to consider that while some people might meet the criteria to be considered disabled per U.S. Census Bureau measures, many people (for whatever reason) might not choose to self-identify as an individual with disabilities. Receiving a diagnosis can often reflect privilege. Going forward it will become imperative to understand how the 2020 Census accounted for people who did not have the opportunity to receive a diagnosis and/or appropriate care due to COVID-19, cultural barriers, medical racism, and more.

These are all questions that must be considered in an ongoing dialogue with the U.S. Census Bureau.

Gaps in Federal Data Collection

Recognizing the significance of disability data to a variety of stakeholders, it is important that this report touches upon the gaps in disability data collection that exist. Demographic information and disability are important because disability is everywhere and may present differently in different groups or subgroups.

Criminal Justice

According to data collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in the 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates, nearly 2 in 5 (38 percent) of state and federal prisoners had at least one disability in 2016 compared to adults in the general U.S. population (15 percent).[viii]

In addition to dealing with stigma and discrimination, people with disabilities are more likely than their non-disabled counterparts to be victims of violent crimes or wrongfully incarcerated. Because there is limited information and suspected underreporting of violent crimes against people with disabilities or people becoming disabled after a violent crime, it is important that federal agencies, particularly the Department of Justice, begin to track more information.[ix] per mandates from the American with Disabilities Act.[x]

Health Care Inequities

People with disabilities are often denied access to equal opportunities, and experience cultural isolation due to stigma, disproportionate education and employment discrimination, and economic inequity.[xi] For instance, there are several health care access barriers for working-age adults with disabilities. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)and Prevention, one third of adults ages 18-44 years with disabilities do not have access to a usual health care provider and have an unmet health care need due to cost. Additionally, a quarter of adults with disabilities ages 45-64 years did not have a routine check-up in the past year.

Additionally, according to a report published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2015, adults with disabilities (40.3%) are four times more likely to report their health to be fair/poor than people without disabilities (9.9%). Because of the vast range of defining characteristics federal agencies have for individuals with disability, the disability community has been largely underrepresented in public health. Without proper identification of the population-level health disparities people with disabilities encounter, or acknowledgement of the diversity within the disability community and its history of discrimination and exclusion, people with disabilities are at greater risk of experiencing disparate health outcomes.[xii]

Collaborative efforts to reduce health disparities, monitor trends in population data, initiate calls for more inclusive data surveying, and improving access and workforce capacity to social services will help improve the lives of people with disabilities.[xiii] Further research from federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) exploring health inequities for individuals with disabilities (including increased data to support decision-making) and explicit inclusion of disability in public health programming is needed to guide policy direction and improve public health outcomes for all.

Different Definitions

Over the past century, the accepted frameworks for conceptualizing and defining disability have changed drastically alongside shifting social perceptions about people with disabilities. The medical model of disability, a framework that was largely popular prior to the 1960s, defines disability as the “result of a physical condition, which is intrinsic to the individual (it is part of that individual’s own body) and which may reduce the individual’s quality of life and cause clear disadvantages to the individual.”[xiv] This approach assumed the position that disability was “unnatural” and was something that needed to be “cured” medically in order to enable a person with a disability to live a “normal” life. Over time, this understanding contributed to the growing stereotyping of people with disabilities.

More recently, society has grown to adopt the social model of disability — coined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001 – which “separates the idea of disability from the idea of impairment,” and considers disability as an overarching term with several subcomponents, including impairments, “a problem in body function or structure,” activity limitations, “a difficulty encountered by a person in executing a task or action,” and participation restrictions, “a problem experienced by a person in involvement in life situations.” This model demonstrates more respect for people with disabilities, through removing the primary focus on the individual’s disability and identifying the “systemic barriers, negative attitudes, and exclusion by society (purposely or inadvertently) as contributory factors.”[xv]

Because of these ranging frameworks and changes in social cultures, another limitation researchers may come across is the wide range of definitions and specific statistics federal surveys have for people with disabilities. For instance, while the U.S. Census Bureau has classified people with disabilities as a hard-to-count population across all their federal research, the definitions of disability vary based upon scope and type of survey they offer. Because The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) covers a larger range of activities in which disability status can be accessed, the SIPP estimates of disability prevalence tend to be broader than the American Community Survey’s more narrow definition. These definitions – and thus survey results – will deviate across other federal agencies and their surveys as well.

Statistically, this can result in differences in findings and unique challenges for federal agencies as “the process of measuring a complex, multidimensional concept in a survey format is difficult,” and “the constantly evolving concepts and perceptions of disability require survey professionals to continuously develop measurement approaches that adapt to new definitions.” In the past, people with disabilities were mainly supported through cash benefits and replacements to earned income; however, today, the focus has transformed to prioritize independence and advance full participation in all aspects of society.

Researchers should consider the purposes for which the disability data are being used and the survey methodologies that are implemented when selecting the collection of disability data that best suits their needs.

Racial Disparities

While there has been an increase in conversations about intersectionality within the disability rights movement, more research exploring the connection between race/ethnicity and disability is needed. As the disability rights community responds to inequities, it is imperative that researchers adopt an intersectional and culturally informed response to ensure that the disability community is advocating for sustainable and equitable changes that will uplift people of color with disabilities. There are currently statistics from surveys such as the 2019 American Community Survey detailing non-institutionalized populations who report disability, which can provide insights to some extent on self-reported disability prevalence (according to the classification of the surveys). However, because of the multiple-identity narratives of people of color with disabilities, it is important for researchers to examine the intersection of race, ethnicity, and disability, and recognize how racial inequities and cultural perspectives on health and disability might influence survey response rates and thus the resulting disability data.

Additionally, it is important to recognize how racialized ableism can disproportionately marginalize Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) with disabilities in a variety of ways including financial inequities, criminal justice, educational disparities, and disparities among racial and ethnic groups. Most of the currently existing data homogenizes racialized experiences and does not disaggregate disability data by race or ethnicity.

Limitations in Research Scope

Aggregated Data vs. Disaggregated Data: The Pros and Cons

When it comes to federal funding, it is important to understand how presentation of the data might impact perception of the data, and thus the validity of a funding request/allocation. Regarding disability, there are many benefits to aggregating data (i.e., combining several smaller elements of data; looking at data holistically), such as through making it easier to identify overarching trends and patterns that exist that would not otherwise be known, and there is in general a greater margin of accuracy, because the data is easier to collect. Disaggregating data, on the other hand, may prove to be insightful in allowing researchers to look for differences that exist between and among important subgroups. However, as a downside, there might not be enough disaggregated data to make any meaningful statements. It is important to take each situation on a case-by-case basis.

What We Show vs. What We Don’t Show: Why can’t we just add questions?

The American Community Survey, Current Population Survey, and Survey of Income and Program Participation only ask about six aspects relating to disability. It would be interesting to see what would happen if in addition to these questions, the survey also asked, “Do you have a disability?” to see what people answer and if there are any disparities there.

Upon discussions with the U.S. Census Bureau, there could be unintended consequences to adding additional questions relating to disability. For starters, the survey language must be as accessible and unstigmatized as possible, otherwise people might select the ‘wrong’ option, and it might not look like there are many people with a disability. Additionally, the survey length might change, making it more difficult for people with disabilities to complete. Lastly, adding in questions only addresses part of the problem. If the surveys are not made more accessible for people with disabilities, then despite having questions added in, the statistics collected might not be an accurate representation of the population, and could compromise necessary federal funding, if the numbers show that the need is not great enough.

[i] https://dredf.org/2020-census-disability-community-toolkit/

[ii] https://dredf.org/2020-census-disability-community-toolkit/

[iii] https://www.dlc-ma.org/the-2020-census-and-disability/

[iv] https://www.ndrn.org/resource/why-are-there-no-disability-related-questions-on-the-2020-census/

[v] https://www.dlc-ma.org/the-2020-census-and-disability/

[vi] https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/disability/

[vii] https://www.census.gov/acs/www/about/why-we-ask-each-question/disability/

[viii] https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/disabilities-reported-prisoners-survey-prison-inmates-2016

[ix] https://www.ncjrs.gov/ovc_archives/factsheets/disable.htm

[x] https://www.ada.gov/criminaljustice/

[xi] https://dredf.org/2020-census-disability-community-toolkit/

[xii] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4355692/

[xiii] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

[xiv] http://www.artbeyondsight.org/dic/definition-of-disability-paradigm-change-and-ongoing-conversation/

[xv] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/icfoverview_finalforwho10sept.pdf

To ensure the accuracy and fairness of federal data and the inclusion of individuals with disabilities moving forward, both federal agencies and disability community must improve its engagement with the other. Federal agencies, including the U.S. Census Bureau, must strive towards improved and increased engagement with the disability community to ensure all persons with disabilities are counted, while the disability community must provide further input to ensure full inclusion in all federal data processes.

Federal Agencies

Enhanced Engagement

To successfully engage with the disability community, the U.S. Census Bureau and other federal agencies who collect and rely on data must provide greater transparency with how data is used and why it is collected. This includes providing plain language materials explaining why data is collected and why individuals should participate.

When conversations are being held related to data collection, methods, outreach and engagement, someone from the disability community should be present to ensure accuracy, fairness, and accessibility in all its forms.

Equitable Access

Surveys and corresponding materials should always be provided in various formats and methods of responding should also vary. In other words, to ensure full participation by every community in federal data collection, agencies should strive to go above and beyond to ensure the full count and participation of every community they tend to count, including the disability community.

Disability Community

Further engagement is necessary to ensure that the disability community not only has accurate data, but to also improve and further the data available.

Community Conversations

The disability community must ask what further data is necessary, and what improvements need to be made within federal data. This can occur through community conversations and must be viewed as a propriety and be done collectively. Decisions related to: (1) what further data needs to be examined and or collected; (2) when aggregated versus disaggregated data is necessary and (3) who the appropriate collector of the necessary data is to minimize fear or confusion from survey participants.

National Advisory Committee and Public Comment

As these conversations occur, it is vital that the disability community provide the U.S. Census Bureau or other federal agencies with specific asks related to the necessary improvements or modifications related to federal data processes, questions, or systems. There are various ways of offering suggestions, recommendations and asks to the U.S. Census Bureau specifically including engaging with the National Advisory Committee (NAC) and offering public comments when requested.

Members of the disability community can attend the Committee’s meetings held at least twice a year and offer public comment during meetings with any feedback. NDRN has offered public comments to the Committee on several occasions urging the committee to ask that they discuss the needs of people with disabilities.[i]

Response to Federal Data Surveys

Along with community conversations and engagement with federal agencies themselves, members of the disability community must continue to participate in federal-led surveys whenever possible! Responses from community members will allow for better representation and resource allocations for every community in America.

[i] https://www2.census.gov/cac/nac/meetings/2019-11/public-comment-national-disability-rights-network.pdf

Collecting and calculating data on every person living in the United States is no easy task. Yet, the American public relies on the U.S. Census Bureau and various federal agencies, including the Department of Education (ED) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to collect, calculate, and disseminate information on communities every year effectively, accurately, and fairly. Collecting data often involves questionnaires such as the American Community Survey, which relies on individuals to respond to questions asked by the Census Bureau, while calculating the data often entails agencies examining what communities might have been missed or undercounted to ensure a complete and accurate count.

Given the tremendous task of counting every person in the United States, it is only fair to assume that certain limitations exist. For various reasons, people are often overlooked or forgotten in the process of federal data collection, including people with disabilities. While significant improvements have been made over the years to count and include people with disabilities, the 2020 Census, alone emphasized the need to do better, ensuring that any federal data collection process is fully accessible, fair, and accurate count of every community in the United States.

This report has highlighted the importance of accurate data, the availability of data on the disability community today, the limitations that exist and what needs to be improved in federal data collection moving forward. Both federal agencies and the disability community need to further engage and collaborate on the best practices on how to be fully inclusive of the disability community in the future to achieve real change.

People with disabilities are in every community, and it is long overdue that federal data collection and calculations do not overlook or forget the disability community.